Stories from the Edge of Music #62: B.B. KING REALLY WAS THE KING OF THE BLUES

B. King on B.B. King

Writer, photographer and pianist Bill King is no relation to the King of the Blues, but he sure understands him.

Unusually, Bill wrote this appreciation of the seminal figure of the blues from the viewpoint of a concert photographer as well as an admirer. He included it, last May, on his excellent Substack

; Bill kindly allowed me to share it with you here. You owe it to yourself to check his elegant writing and brilliant photography here.I’ve added three quick postscripts of my own, since I was only the second person to bring Mr. King to Canada, back in 1968.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

B.B. KING: AN ARTIST WHO NEVER GOT OFF THE BUS — EXCEPT TO PLAY HIS HEART OUT ON STAGE

BILL KING

If there were ever a musician I’d give anything to have a long, unrushed sit-down with—just two chairs, maybe a couple of Cokes, no entourage—it would be B.B. King.

I fell for the King the moment I dropped the needle on Live at the Regal. The vinyl spun, and there it was—those stinging guitar licks that sounded like they'd been pulled from the gut of every broken-hearted man south of Memphis. B.B. left space between the phrases like a preacher between parables. Empathy oozed through his strings, but so did control. Nothing accidental. Nothing wasted. The voice? Always on. Always gospel. And the guitar—Lucille—well, she spoke back in perfect time. Voice and guitar weren’t separate; they were two ends of the same soul.

B.B. was from that rare tribe—the ones who never got off the bus. Willie Nelson, Dolly Parton, B.B. King. Lifers. I’ve ridden those buses too. I know the allure: the rhythm of tires on asphalt, the late-night diner pit stops, the bunk stacked above the hum of the engine. But for a lifetime? That’s a calling only the road-wired few ever answer. B.B. didn’t just learn the circuit—he became it.

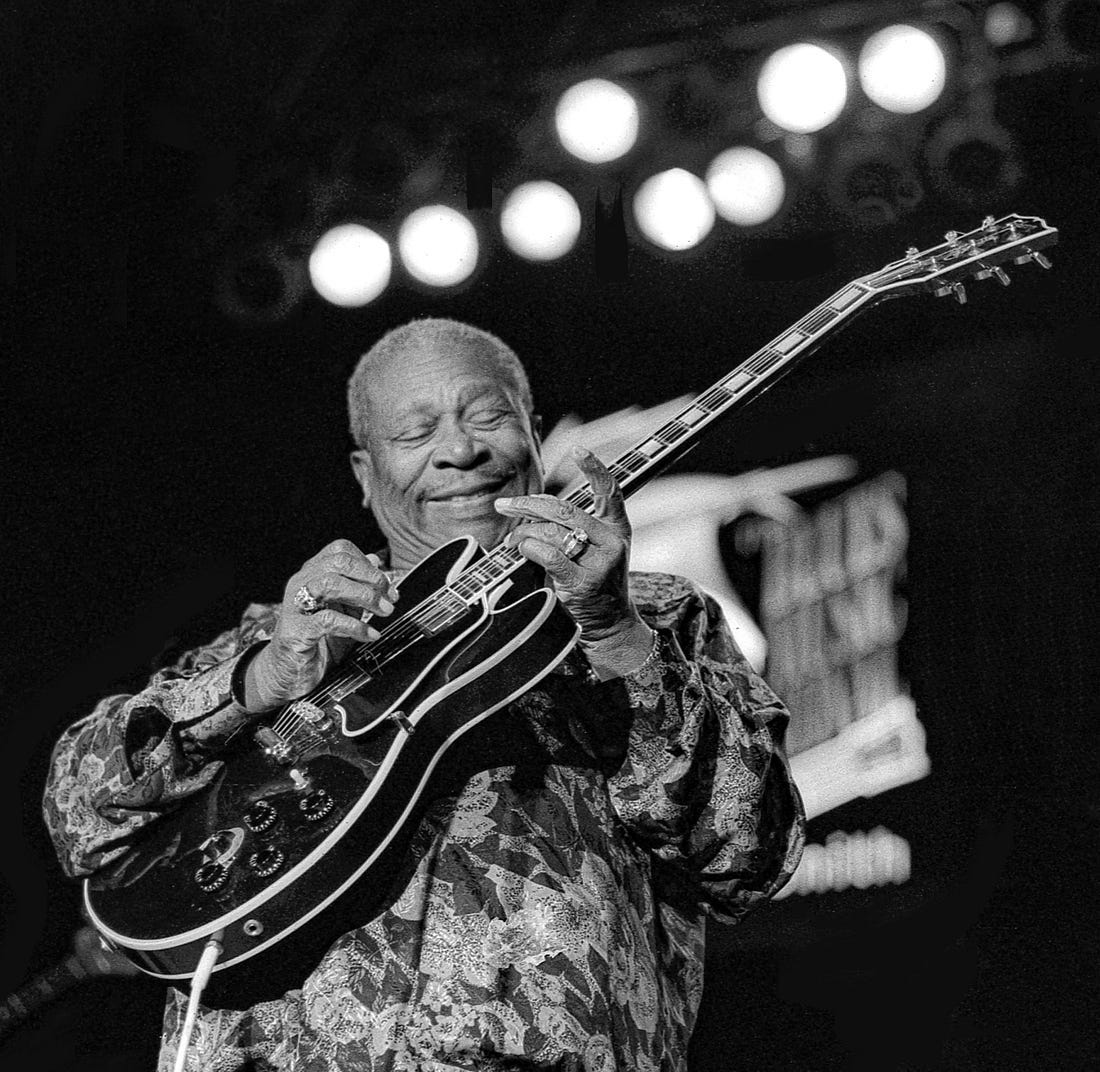

When I had my first opportunity to photograph him in 1998 at the Molson Stage in Toronto, it was a chaotic scene in the photo pit. One minute—that’s what we were given. I came loaded for war: two camera bodies, both loaded with 400 ASA black-and-white film. The Jazz Report Magazine had me in, and I wasn’t there to fumble.

The band came out first—a warm-up jam that let me dial in—F-stop, shutter speed, lens focus—old-school. I spotted the amp dead centre and locked in my vantage, away from the eager elbows of the dailies.

Then B.B. arrived.

You could feel him hit the stage before you saw him. The audience surged to their feet, just like on a Sunday morning in church. And King—he understood the moment. He gave the camera what it needed: arched brows, half-grins, eyes closed in prayer, or maybe pain. Those facial expressions were as much a part of the music as Lucille’s cry. Some were for the camera, yes—but many were genuine, born of that intimate space where sorrow and survival meet.

I kept shooting—one body, then the next. Thirty frames in, the second roll was almost gone, but I was in the zone—inside the moment. And then, the perfect closer: B.B. lifts Lucille skyward, cradling her like a daughter, holding her up to the heavens—or the balcony, at least. I hit the shutter on the last frame. Some say that the guitar wasn’t the Lucille—maybe it had been gifted to a pope along the way. Didn’t matter. In that moment, it was every Lucille he ever carried.

The last time I saw him was in July 2014. By then, B.B. was talking more than playing. But that was just fine. He’d earned the right. He was still there—alive, joyful, still busing it and still giving.

Artists like B.B. don’t fade. They imprint. Like Buddy Guy. Like Tony Bennett. They live in two registers: sound and sight. Once you hear, sure—but the other stays with you like a photograph burned into memory. Not just notes and lyrics, but posture, gesture, that tilt of the head when the solo comes. They give in stereo. They give everything.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

THE KING AND I: THREE QUICK POSTSCRIPTS

I often tell people that I was the first promoter to bring B.B. King to Canada. Not quite, though it’s better story that way.

The fact is, two weeks before King’s Massey Hall debut (February 14, 1968) and his first show in Toronto, he appeared at the 700-seat Grand Theatre in Kingston. I drove down with Adam Mitchell, former lead singer of of the hottest band in town, the Paupers, and with Buddy Guy.

My best memory of that night was watching Buddy sit in. No guitar histrionics, no grandstanding: the Young Pretender was calm, restrained, and was the perfect partner for the King.

As a boy promoter, I was blessed with horseshoes embedded in my rear. Massey Hall did not ask for a deposit; Joe Cartan, the manager, simply trusted me.

And between the time I booked King through the nice lady at Duke Records in Houston (“Gee, you talk so funny,” she told me) and the time the show happened, the bluesman had his only crossover hit, “The Thrill is Gone.” Tickets were $2.50, $3.50 and $4.50; the show was sold out.

++++++++++++++++++

I never realized that I had become what’s known as the “promoter of record” for King in Toronto — the unspoken tradition by which you have first dibs on an artist's future concerts.

Soon, King was appearing in clubs and bars all over the city, and on one run through town he called me at home. “Do you know Lonnie Johnson?” he asked. “He’s my favourite guitarist, and we’ve never met.”

I called Howard Mathews, one of the owners of the town’s only soul food restaurant, who knew everybody in the Black community. “Do you know where Lonnie Johnson is?” His response: a simple “Yes.”

“So where is he?” You could almost see Howard’s grin as he replied: “He’s in my kitchen.”

I picked King up, drove to Howard’s house and walked him into the kitchen. Lonnie Johnson was indeed there, and so were two other legendary bluesmen, Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee. I made the introductions and left the room; I felt I had no place in a room with four people who I had admired all my life.

+++++++++++++++

A few months before he died in 2015, King once again played Massey Hall — now an annual visit. For no reason that I can recall, I was backstage, his band was opening the show, working through the play-on number.

King, his guitar on, was standing at the door that leads to the stage, waiting to walk on. He spotted me, beckoned me over, and gave me a warm hug. “You must have lost money when we did that show here all those years ago.”

“No, B, I actually made $700,” I said. “You set me on the road to ruin.”

“Happy to have helped,” he laughed. I opened the door for him; he walked on stage, and hit the first brilliant, stinging note…

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Stories from the Edge of Music to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.