Stories from the Edge of Music #41 Downchild Part Two: Good Times Guaranteed

Canada’s Downchild Blues Band is packing it up after a half-century of rockin’ music. Here’s the success story of a now-legendary band

My excuse for delays in getting these stories to you is not that my dog ate my notes (I don’t have a dog) but that life gets in the way, especially in the summer. After four festivals in Western Canada I was exhausted, and then I needed to make an unexpected trip to northern Michigan with my family.

But we’re back now, with the second part of the Downchild story. But there’s more: a B.B. King story sent by a new reader), some cool video links, and (via this week’s quote) our first foray into American politics. Yes, I know that’s none of my business, being a Canadian and all, but we’re all going to be buggered if November 5 doesn’t turn out right. Or left, let us pray.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

HOW SUCCESS CHANGED DOWNCHILD

After packing the El Mocambo in Toronto for a whole week every three or four months in the early 1970s, the Downchild Blues Band played week-long gigs in London and Windsor and North Bay and Sudbury and Kenora and Wawa and Winnipeg — all the way to Vancouver and back. There was a trip to a festival in France, and an underpaid gig at the New Orleans Jazz Festival.

Other highlights are still remembered, like the show in a long-defunct venue in Vancouver called O’Hara’s; more than 1,200 people packed the joint. The band took the door money and a small percentage of the bar income.

With more than $14,000 cash in the briefcase, Walsh hosted an after-party at one of Vancouver’s most respectable hotels, complete with an array of drugs and several enthusiastic and willing groupies. Surveying the room as I fondled two lovely blondes on the suite’s chesterfield, I thought: music, alcohol, cocaine, naked women — this is the rock and roll life. I liked it, back then, a lot.

Success, however, came with an inevitable toll. The band was now playing close to 300 nights a year and exhaustion and frayed nerves multiplied with the miles on the road. The rock and roll adage that if the musicians are still talking to each other after close quarters in the van, shared rooms in cheap hotels and sketchy gigs in unsuitable venues, then you have a band.

Otherwise you have a constant turnover of players.

By a generous count, more than 100 players passed through the Downchild ranks in the early days of its success. Some quit, unable to take the constant touring. Some got fired outright: there were band meetings when Walsh would announce he had good news and bad. The bad news was that a member would be let go; the good news was that the rest of the players would get a raise.

One of the early casualties was bassist Jim Milne, who kicked out the side window of the van on the way back to the hotel after a disastrous gig at the Philadelphia Folk Festival. That night the band made up for it and played a magnificent set at the performers’ party, but by that time Milne had broken his toe kicking in the bathroom door in the hotel.

Afterward, a number of the performers and guests broke into the outdoor swimming pool at 3 a.m. Hock Walsh did a cannonball from the top diving board, almost emptying the pool and perhaps providing the inspiration for “The Swimming Song,” written by Loudon Wainwright, another participant in the late-night party.

Once, on an 11-hour drive between Windsor and a daytime show in Ottawa, Donnie — who always drove the van —pulled over on the shoulder of the highway and turned to his grumbling, exhausted musicians. “Anyone who doesn’t want to play this gig can get out now,” he pronounced, and they all did; Walsh drove off, missed the show, and returned home.

“Embarrassing,” he said later. ”I had to hire them all back the next morning.”

The most serious change was the departure of Hock Walsh. For all his dry off-colour humour and his general fecklessness, he was the perfect foil for his brother; his distinctive voice had played a major part in the band’s success. With less than a week before recording was to start on the follow up to Straight Up, Donnie Walsh sacked his brother.

“How the hell do you fire your own brother?” I shouted on the telephone when I heard the news; his co-managers had not been informed in advance. “Oh, I just said, ‘Hock, I’m letting you loose.’ And that was that.”

The band’s popularity continued, however. New singer Tony Flaim was a workmanlike addition, and hiring another new recruit to the band, pianist Jane Vasey, turned out to be a brilliant move.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Classically trained Jane Vasey played up a storm with the band for more than 10 years. And she played well with others — here she’s with the band (minus the leader, Donnie Walsh) on the Peter Appleyard television show

The “chick in the band” melted hearts

After Donnie Walsh himself, Jane Vasey was perhaps the most remarkable player in the band’s long history. Petite, blonde and green-eyed, she melted the hearts of everyone who saw the band between 1973, when she joined, and 1982, when she died of leukemia.

Classically trained, she had fallen in love with the blues when a friend played her a record by Otis Spann, the long-time pianist with Muddy Waters. “I’d listened to blues before, but not too much,” she told an interviewer. “But Spann’s playing seemed to involve a lot of the things I loved about classical music — great runs and phrases I could instantly relate to.”

Perched behind the piano at the left of the stage, an ever-present glass of cognac within reach, she sat upright and sparrow-like and delivered simple and powerful New Orleans-based boogie-woogie with a toss of her hair and a smile to fall in love with.

The fans called her “the chick in the band” and the players still recall how the audience would stand, if they could, to the left of the stage where they could watch her close up and drink in her smile. She became the glue that held the band together and the kid sister for the band members on stage. She held her own with anyone in the band when it came to living on the road, but she always managed to look fresh and bright and perky the next morning.

Diagnosed with leukemia shortly after she had joined Downchild, she retained her sunny personality, and the force and power of her playing seemed to increase rather than diminish. Hardly anyone knew she was sick. The radiance of her smile betrayed no concern at all.

As the ’80s began, her illness became more of an issue, but Jane never missed a gig although she often flew to distant shows while the band crammed into the van. By then, her treatments (“they just change my blood around,” she laughed) were more frequent and more exhausting.

One of her last gigs — at a rare time when Downchild was off the road — was as a member of a pickup band engaged for a week at a bar called Albert’s Hall. Hired to back up Eddie “Cleanhead” Vinson, a popular blues shouter who had made his first records some 40 years before, she missed a treatment because she would have needed a day or so to recover. As the six-day gig went on, she looked tired, her pale skin became more translucent, and her green eyes seemed even greener.

Years later, I interviewed Vinson, and asked if he remembered her. “Don’t even mention that girl,” he responded. “She was so good, so beautiful, and she did not need to go that soon.” A few months after that, Vinson himself succumbed to cancer.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Marking the band’s history, decade by decade

As the years passed, the band continued to criss-cross the country, with occasional forays into the United States. Their publicist did his best to generate interest, in part helping to come up with slogans like “Canada’s Blues Band” and “Good Times Guaranteed” — but Downchild was becoming part of the Canadian music business scenery, well-regarded but taken for granted. There were moments when the media could become interested again, as they did when the band, on its 25th anniversary, returned to Grossman’s Tavern, bringing back old friends, acquaintances and former members for 10 days of raucous music.

Hock sang with the band again, and Vic Wilson (then co-managing Rush, the biggest rock group in Canadian history) picked up his sax to reprise his part on the original recording of “Flip Flop and Fly.” Jeff Healey’s power blues-rock trio deafened the audience. And CBC-TV, at the last minute, fashioned an hour-long Downchild special, featuring Indigenous blues singer Murray Porter and now world-famous producer Daniel Lanois.

The show was hosted by Adrienne Clarkson, who later became Canada’s Governor General. She didn’t come to the event, and later taped her introduction to the show (lifted completely from the bio I had written for the band) with an attitude of supercilious disdain.

The band played fewer and fewer dates in the ’90s — by the turn of the century the days when bands had week-long engagements were a distant memory. The band was making its transition into festivals and concert halls, rather than gritty blues bars, and its price went up accordingly.

There were highlights, including a 2007 live recording session at the Palais Royale, an old-style dance hall on Toronto’s lakeshore. By now, the band had settled into a steady groove with an stable lineup of players. Chuck Jackson was the singer and an adequate harmonica player (the harp battles between him and Donnie were always a highlight of the show), and the others had been in the band for well over a decade without change. Michael Fonfara was a solid keyboard player, Pat Carey was a rocking tenor sax man, Mike Fitzpatrick occupied the drum chair, and Gary Kendall was the bass player.

Kendall, by far the least demonstrative musician on stage (much like the Stones’ Bill Wyman) played standing stock still with a studious expression on his face. As a packed house danced at the Palais, I noticed that Kendall was grinning from ear to ear; the band was having an explosively good night. And Live at the Palais Royale stands up as one of the best live recordings ever made in Canada.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

40 years on, a chance for a revival of interest

On the band’s 40th anniversary, in 2009, there was a chance, once again, to earn some well-deserved national media attention. A tour of major cities was planned, with a Massey Hall date in Toronto featuring blues veteran James Cotton and Canadian guitar stars Colin James and Colin Linden, as well as Dan Aykroyd and Wayne Jackson of the Memphis Horns. The hall was sold out, and the band delivered a show that was filmed for a Bravo TV special and a DVD release.

Two months before, over coffee at my local restaurant, Donnie had fired me. As a consolation, he offered me the opportunity to handle the publicity for the Massey Hall concert; I insisted that I would need to handle the entire tour or nothing. He passed, and an inexperienced young publicist was hired to promote the tour.

And so, after 39 years and on my 75th birthday, I lost a friend as well as my longest-running client.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Downchild says farewell

When COVID struck, Downchild went on hiatus. A 50th anniversary tour was arranged, scrapped, rescheduled and scrapped again.

Hardly any bands last this long, and the trajectory from “unknown” to “famous” to “legendary” had taken the band half a century.

Now, the band has finally decided to quit. There’ll be a farewell tour, a final kick at the can, a chance for Downchild fans to say goodbye.

It’s been a great run. Good times were guaranteed, and almost always delivered. And the stories and the memories will live on, at least in Canada.

The original Blues Brothers are outta here…

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

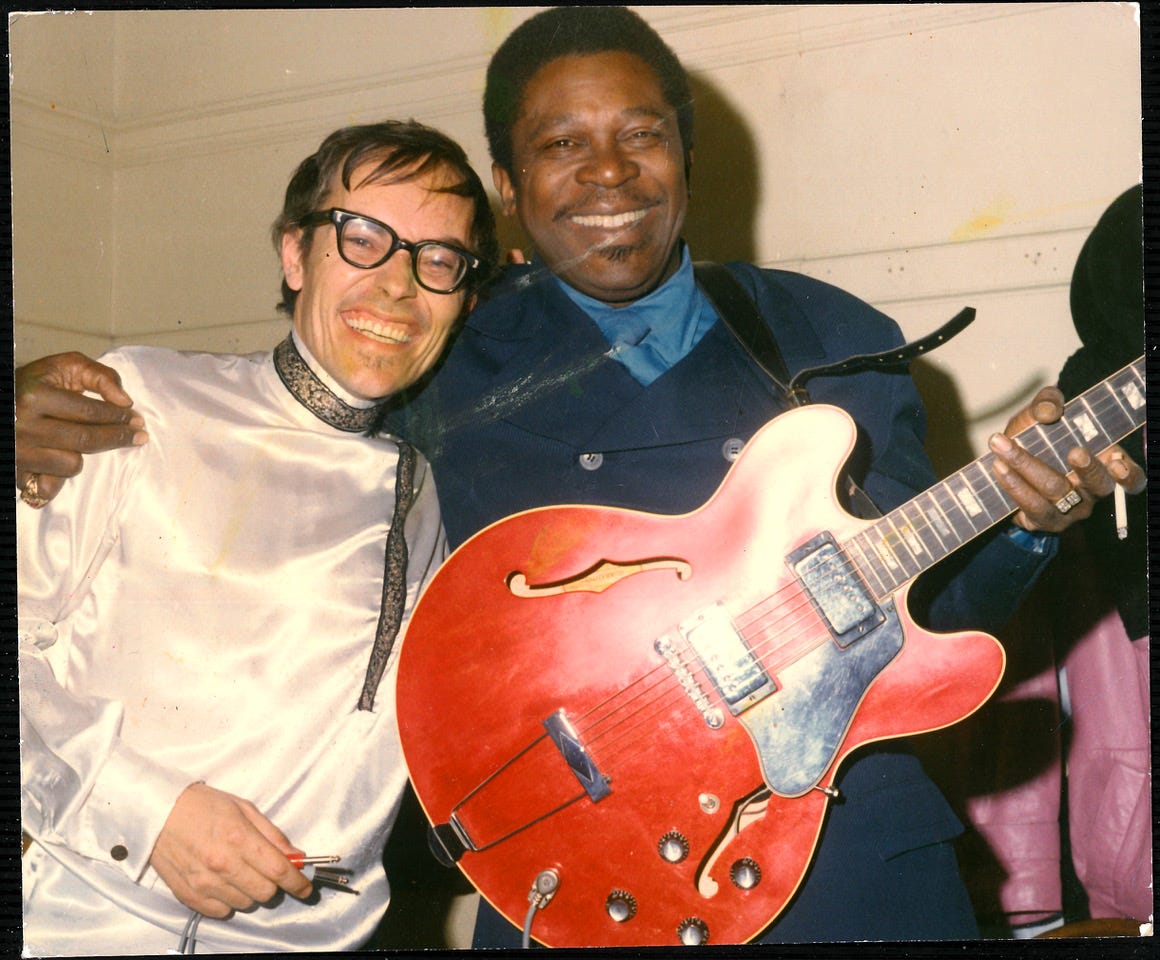

A B.B. KING STORY FROM A READER

Kit Cross, an old friend who lives on Vancouver Island — when she’s not leading adventure tours around the globe — used to be an excellent sound tech.

She sent me this B.B. King story. It’s a pleasure to share it with you.

“When I was about 17 (and likely my first year as the tech director of the Mariposa Folk Festival, by the way!) I was the house engineer at the Colonial Tavern on Yonge Street in Toronto, the club for week-long appearances by American artists.

“I was a bit nervous about looking after the gear in the club. I had been told I’d better make sure nothing was blown up by travelling sound guys. During my time there, we did Dizzy, Stan Getz (that’s where I picked up a European tour with Getz), Muddy Waters, Captain Beefheart and a pile of others.

“B.B. King was one of them. When he came in, I went into the dressing room to ask if he was carrying a sound guy. He looked me straight in the eye and said, ‘Who does sound for the club?’ I said it was me, he looked around and pointed to a guy on the other side of the room and said, ‘It’s him—he’s my sound man.’

“So the two of us headed out to do sound check, set up some mics and I handed the system over to him. Couple of minutes later, the guy turned back to me and said, ‘Man, I don't know what to do with this!

‘I drive the damned bus!’”

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

QUOTE OF THE WEEK

“News flash: Trump isn’t ever going to change. He’s incapable of it. He’s the same person he was eight years ago — a racist, sexist, greedy, power-hungry, low-wattage imbecile with a toddler’s understanding of the world, no impulse control, and the attention span of a coked-up squirrel.” —

’s Substack column , Aug. 19, 2024+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

VIDEO LINKS FOR YOUR WEEKEND

So many musical highlights this summer — but nothing compared to the final artists at the Edmonton Folk Music Festival, Robert Plant and Alison Krauss. Here’s a fan’s view of the pair, recreating an old Led Zeppelin classic.

This has been William Prince’s year. This gentle giant of a man offers intimate songs at major festivals to hushed crowds. Everyone who listens to him, or meets him, is almost overwhelmed by his warmth and his aura of friendly kindness. Here’s a mini-documentary of his debut at the Grand Ole Opry.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

SEE YOU NEXT TIME

That’s it for another week. Thank you for reading — your comments are always welcome. So, too, is a little bit of financial support, if you can manage it. Paid subscriptions — $6 each month — support this Substack. And may even help pay for a newer computer, since this one is on its very last legs!

Richard, I'm still annoyed that I never saw Downchild. They were booked to open for George Thorogood in Ottawa around the mid-1970s, and didn'd show (actually I'm reminded that they *did* show, about the time George was going back on after his intermission).

live at the elmacombo is for my money one of if not the best lp Downchild did,funny you never really talked of David Woodard on tenor sax who was a fine fine player and went on to have great years with another popular blues band ,Powder Blues........keep the Flo coming bro........