Stories from the Edge of Music #40: The ORIGINAL Blues Brothers

Canada’s Downchild Blues Band is calling it quits after a half-century of rockin’ music. The first of two parts: Straight Up.

There’s much more this time, now that your correspondent has (mostly). recovered from being at four Western Canadian music festivals in four weeks. Please read on for stories about folk festival founder Mitch Podolak,

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

WELCOME TO A TIME MACHINE: A TORONTO BAR IN 1969

Grossman’s Tavern is crowded. We’re on Toronto’s Spadina Avenue, traditionally the street that’s been the city’s “reception area” for waves of new immigrants —European Jews, Chinese, West Indians, Hungarians and more recently Vietnamese.

The tavern owner is a diminutive man called Al Grossman, and he runs a pretty loose ship. If you want to smoke a joint, he doesn’t care. If you get drunk and obnoxious, one of his giant waiters — a linebacker of a black man called Rocky — will gently throw your ass onto the street.

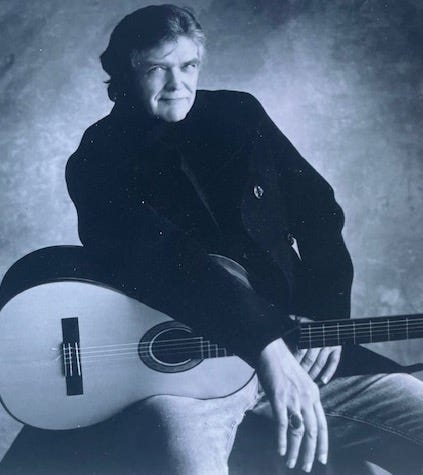

The band on the makeshift stage in the corner is the Downchild Blues Band, named after a lyric in a song by Chicago blues harmonica master Sonny Boy Williamson. The group is fronted by Donnie Walsh, a slim guitarist who also plays harmonica, and his brother.

Known as “Hock” — as in ham hock — Rick Walsh is the band’s barrel-chested singer, armed with a dry sense of humour and a distinctive voice. As I wait to order a beer, I check the rest of the band: Gary Stadolak, known as Beeb, plays rhythm guitar, Dave Woodward is on tenor sax, Jim Milne plays bass and Cash Wall is the drummer. Tight band, with a decent repertoire of Chicago blues standards.

But getting a beer isn’t easy, and finally I accost the large waiter. “Hey, what does it take to get a beer around here?” I ask with some irritation. His response is fast: “Out!” he says. “You’re barred! Out! Sling your hook!” As I shuffle out the front door, Al Grossman whispers, “Come back tomorrow; it’ll be fine.”

I did, and it was, and I began a 39-year relationship with the band — as co-manager, publicist, occasional touring companion and friend — ending only when Donnie fired me on my 75th birthday.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

How Downchild set an example for other artists

In 1969, the “independent” recording scene in the United States and Canada was in its infancy. If you were a band, or a singer, and your music was not considered likely to be commercially viable, you were out of luck. Certainly, none of the major record companies would be interested in a blues band whose only experience was playing at a down-at-heel Toronto bar.

So the band and its managers — and I was now joined by my friends David Bleakney and Jim McConnell — would take a revolutionary step, and make our own record. With a budget of $500, Downchild assembled in a tiny “studio” in a corner of the second-level underground parking garage of Rochdale College.

(Rochdale, a “free” college loosely affiliated with the University of Toronto, was originally run by friendly weed-smoking hippies, but was soon overrun by bikers, much heavier drugs, and newspaper headlines about LSD-inspired residents who figured they could fly, and jumped off the 12th-storey roof to prove it.)

Sound Horn, named after the warning sign at the sharp turn as you entered the garage, consisted of two small rooms; it was certainly one of Toronto’s tiniest studios. The control room contained a two-track Revox recorder, and was divided from the main room by a wall of opaque glass bricks. Bleakney, McConnell and I were crammed into the small room, and the band in the other room, gathered around two microphones.

The best way to make this record, given the primitive surroundings and our two-track recording machine’s limited capabilities for over-dubbing, was to record every tune in the band’s repertoire twice.

With a couple of bottles of Johnny Walker, and two long sessions on successive nights, the band had recorded two versions each of some 20 tunes. Within days, we had rejected almost all of them —nine were usable, in tune, and contained no obvious mistakes. A close-up shot of Hock’s army-boot-clad feet was the cover, and we called the album Bootleg. Freelance writer Jack Batten, then contributing jazz criticism for The Globe and Mail, wrote the sleeve note; we had 500 copies pressed up, and went out to sell them.

The first out-of-town gig the band played was in Milton, a distant Toronto suburb; the band played a storming set to an indifferent audience in a sports bar. There was only one minor fight, and we sold four copies of the album for $5 each. It was going to be a long time before the costs of this one — two bottles of whiskey and $500 in studio costs — would be recouped.

However, two weeks later Bleakney got a call from Barry Keane, the A&R man at RCA Records (and afterwards, for many years, Gordon Lightfoot’s drummer). Could RCA take over the distribution of the record and re-release it? Would $2,000 be enough to do the deal?

The band celebrated, Donnie and Hock got drunk, the management team congratulated themselves, and RCA managed to get the record released — to complete Oriental indifference — in Japan.

All these years later, you can still find that record. Amazingly, it still sounds pretty good.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

The album that inspired Saturday Night Live’s Aykroyd and Belushi

It was Downchild’s second record that really launched the band. Simply titled Straight Up, the album had a striking cover of a shot glass filled with whiskey — a pretty accurate portrayal of the band’s hard-drinking image at the time.

Recorded in the laundry room of his mother’s house in Hamilton, the record was engineered by Daniel Lanois. (Thanks to his work with Brian Eno, U2, Willie Nelson, Emmylou Harris and Bob Dylan, Lanois later became one of the most famous producers in the world.) But the producer of Downchild’s sessions in the laundry room was Billy Bryans, who went on to help start Parachute Cub, one of the most enduring of Canada’s ’80s bands.

Best of all, Straight Up had a genuine hit. “Flip Flop and Fly” — originally an R&B hit for blues shouter Big Joe Turner in 1955 — became a staple of Canadian-content radio, and is still played on “golden oldie” stations. It’s also a song the band has had to play at every single gig for close to 45 years.

Meanwhile, the band established a friendly relationship with Dan Aykroyd, who ran an after-hours downtown boozecan on Queen Street where Walsh and his brother drank, and occasionally played, after their local gigs. Regular guests included the Second City cast, CBC radio and television personalities, late-night sex workers and waiters and even the odd policeman.

Aykroyd became a member of the Saturday Night Live cast in New York, and enthusiastically shared Downchild’s Straight Up record with a fellow cast member, John Belushi. The Blues Brothers, inspired by Donnie and his brother, was originally created for a comedy sketch on the show, and turned into a phenomenal success.

Belushi’s and Aykroyd’s debut album, Briefcase Full of Blues, was released a year after Straight Up, copied the Toronto band’s sound perfectly, and also contained two Downchild songs. The records sold millions of copies, and the royalties have continued to accrue to Walsh, through his publishing company, Downchild Music, for more than 40 years.

And even the Blues Brothers’ iconic briefcase had a connection to Downchild — Donnie had found a battered case in a dumpster, and years later it was featured on the cover of Ready To Go, the band’s fourth album. “I carried that damn case around for years, because I was now the bandleader,” he said. “I thought the boss better have a briefcase.”

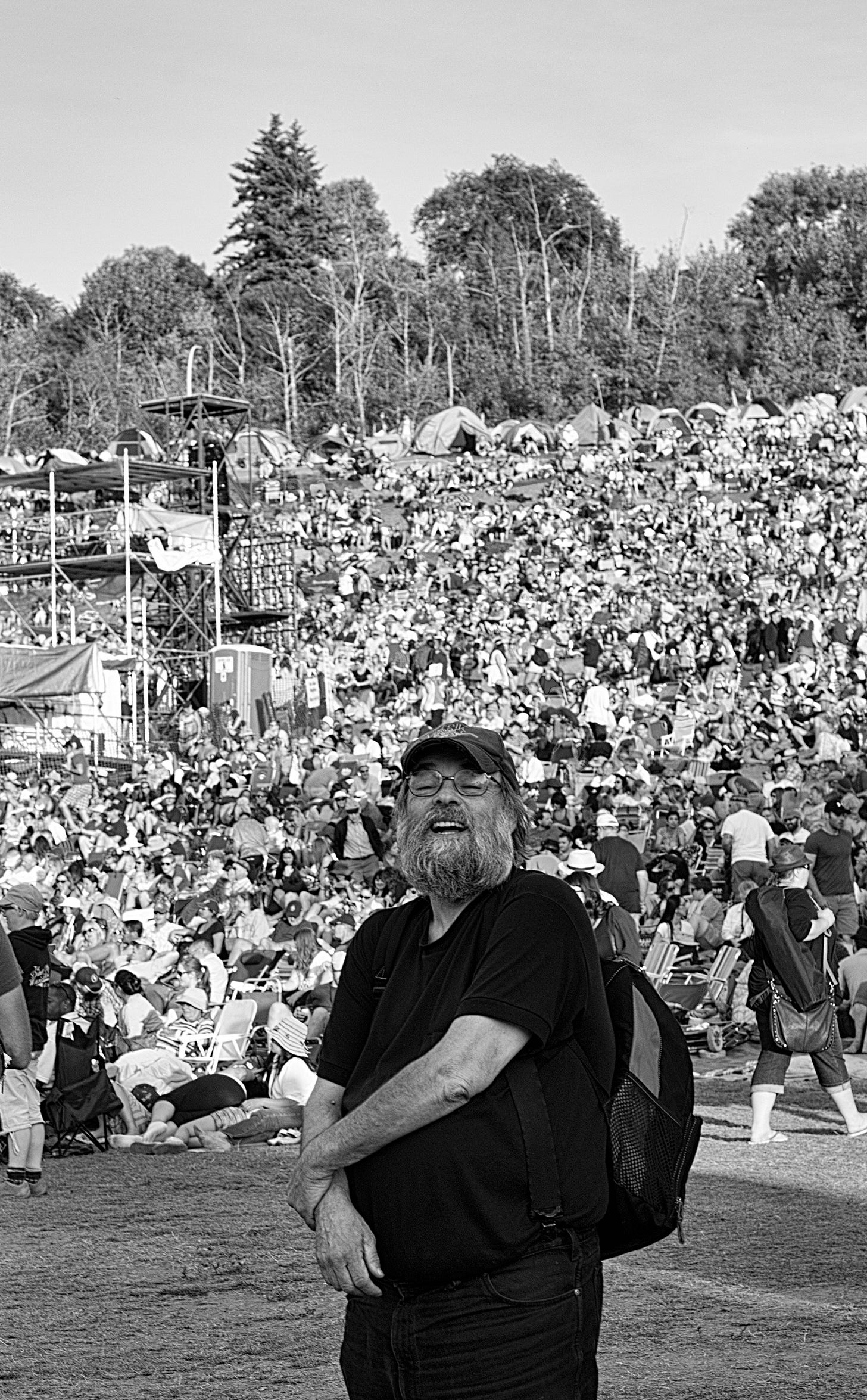

Downchild literally closed the city’s fashionable Bloor Street area during the Toronto Jazz Festival four years ago. Their special guest was powerhouse guitarist and singer David Wilcox (white shirt).

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

THREE QUICK STORIES ABOUT A MUSIC FESTIVAL PIONEER

Bearded, rotund, stubborn, often bloody-minded and always politically far to the left of centre, Mitch Podolak was a visionary. He founded the Winnipeg Folk Festival and the city’s West End Cultural Centre in 1974 and helped start the Vancouver Folk Festival four years later. In addition to a flourishing career as a producer and host for CBC Radio, he was instrumental in helping establish the Stan Rogers Festival in Canso, Nova Scotia, and Summerfolk in Owen Sound, Ontario. He died on August 25, 2019, and will always be remembered with affection in the North American folk music community.

I wrote these stories five years go for a Canadian music industry publication and they strike me now as way too self-reverential. I hesitated about reprinting them again, but I promised them a couple of weeks back, so here they are, slightly cleaned up.

A phone call that helped kickstart a festival

In 1973 Mitch Podolak, out of the blue, called Estelle Klein, the artistic director of the Mariposa Folk Festival in Ontario. Could she offer advice on how to run a festival?

Tired and probably talked out after her own festival, she requested a fee for her advice and counsel. Hearing this, I took it on myself to phone him in her stead, without a fee, and offer what help I could. I spoke about the need for a committed crew of volunteers, the need to have a wide variety of different kinds of “folk” music, and performers from disparate communities, including First Nations artists and people of colour, and the need for artists from other countries, and other parts of Canada.

I can’t remember the details, but I do recall that — well before long-distance plans were devised — my phone bill that month was seriously expensive.

For years afterward, Podolak recounted the call, doing a less-than-flattering imitation of my English/Transatlantic accent. When I asked him to stop, he told me, amiably enough, to fuck off; he said the story was better with his imitation, however badly it irked me.

How “Americana” songwriter Guy Clark came to Canada

Long before Guy Clark won his reputation is one of the best “Americana” songwriters, a friend in Los Angeles sent me a tape of four of the songs from his first album, Old No. 1, which had not been released in Canada.

I sent copies of the songs, with an enthusiastic note, to Podolak. Several months later, in 1984, he booked him. Arriving at the Airport Inn — the decidedly low-rent motel which served as accommodation of all performers and guests — I met Clark, and his gracious wife Susanna. It was their first visit to Canada.

Podolak pulled me to one side. “Is he any good?” he asked. ”What’s he like as a performer?” I had no idea — but I reiterated that he was a wonderful songwriter.

“Well, he’d better be good, because he’s closing the show tonight,” Mitch said. ”If he’s lousy I’ll kick you in the balls.”

Clark triumphed, and went on to play the festival four more times, once in collaboration with his best friend Townes Van Zandt.

Electric instruments at a folk festival? No way

Even in the late ’70s, Mitch had a cast-iron rule: NO electric instruments on stage. That would open the folk world to rock and roll; the thin edge of the wedge and definitely not in the Pete Seeger wheelhouse. There was one exception — Stan Rogers’ accompanist did play an electric bass, albeit through a very small amp.

I’d arranged that one of Canada’s greatest guitarists, Amos Garrett, would play the festival acoustically, and so he did — until he pulled out his trusty Telecaster for the last song, and played a superb version of his signature tune, “Sleepwalk.” It was the first time an electric guitar had been heard at the Winnipeg Folk Festival.

Mitch was furious, blamed me for encouraging Garrett to break the rule, and refused to talk to me for months. Eventually, thanks to the intercession of Rosalie Goldstein, the woman who later became his successor as the festival’s artistic director, we kissed and made up.

And Garrett, who led the house band at the Edmonton Folk Music Festival for more than 30 years, eventually went on to play the Winnipeg festival three more times, once Podolak abandoned his self-imposed and ill-advised rule…

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

VIDEOS TO LAST YOU TO NEXT TIME

Next week, I’ll mutter about the amazing music I heard on the festival circuit this summer. Meanwhile for the handful of readers who open these videos, here are a couple of artists I discovered this year (better late than never).

First up, a too-short clip of an artist who killed at both the Calgary and Edmonton festivals. Meet Fantastic Negrito:

This is NYSSA, a punk power poet with stage presence to burn. If commercial radio had balls, this would be a hit. I’m in love, OK?

No “discovery” for me, since I’ve known Andrea Ramolo for close to 20 years. She’s just wound up her second Canadian tour with Kalascima, an astonishing high-energy band from southern Italy. This is a more reflective piece that’s an acknowledgement of Andrea’s own Italian heritage.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++≠≠≠≠≠≠≠++++

QUOTE OF THE WEEK

“The key component to being a functioning, creative musician and songwriter is to never, ever, under any circumstances, grow up. You grow up, your art is done. It’s over.” — Mark Holmes, founder of Canadian rock band Platinum Blonde, quoted by Nick Krewen in The Toronto Star.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

NEXT TIME AROUND…

The second part of the Downchild story — more stories of the band that inspired the creation of the Blues Brothers. There’ll be details of their “farewell tour.” I’ll also tell you some of the highlights of my five-festival musical summer. Oh, yes, and there’s a funny postscript to our recent B.B. King piece...

If you’re enjoying these Stories from the Edge of Music — and we add some 30 new free subscribers every month — it would nice if you’d consider upgrading to a paid subscription. Your contribution of a mere $6 a month would help me sit in my local Starbucks and think of more tall tales to tell you.

Amazing journey through the early days of the Canadian music scene. I left America in June, 1971 right after my 21st bday. Because of the movie, Easy Rider, I decided to hitchhike across Canada to NYC and on to my goal of London. I was in Vancouver and Toronto that summer and went to a number of music gigs. I also landed in Calgary during the big rodeo, which for a hippie from SF, was quite a scene and a bit scary. My memories of Canada in the 70's have always been a bit wild and wonderful.