Stories from the Edge of Music #33: Personal stuff (Part 1) — a boy reporter learns how to tell true stories

And other Substacks I’m reading and why

I’ve been thinking ‘bout the relationship between those of us who write Substacks, and those of us who read them. I’d like to believe — and I hope you’ll let me know if I’m wrong — that there’s a strong bond between writer and reader. And that bond, I hope, allows me to share some personal stuff outside the stricter boundaries of the Substack I began more than nine months ago…

NEWSPAPERS ARE VANISHING. HERE’S HOW IT WAS BACK THEN

At 16, fresh out of boarding school, I was hired as a trainee reporter by the daily newspaper in York, a historic city in the north of England, and 12 miles away from my safe, upper middle-class home with my parents.

Salary: £3 a week, paid every Friday at noon. Job description: attend two afternoon and two night school classes a week (typing, shorthand, an overview of legal issues, political studies). Undertake two night assignments each week, work five days covering shopping news, court proceedings, council meetings. And spend Saturday afternoons covering football or cricket matches.

Journalism school? A North American concept, apparently: in Britain in the ’50s, each newspaper hired one or two junior reporters a year, and attempted to teach them everything they needed to know. If they got through the three-month probationary period, their apprenticeships continued for a total of three years.

My first assignment was to compile the weekly shopping notes. “Go to the greengrocer’s shop on Parliament Street,” said the tall, cadaverous chief reporter, Gordon Kilvington. “Write down the prices of potatoes, fruits and vegetables. Get back here in 20 minutes, type it up, write an opening sentence, and have it done in an hour…

“Oh, and don’t make any mistakes. This list is what all the other food shops in town set their prices by.”

The local newspaper: Then the most important voice in town

The Yorkshire Evening Press was the most important voice in York, a historic city in the north of England with a population, then, of 100,000. The fact that the paper sold some 40,000 copies a day in the city and the outlying areas gives you an idea of its role in the community.

In the ’50s, the major daily newspapers, all out of London, covered the national and international scenes. The Times was still the newspaper of record, The Daily Telegraph was (and still is) staunchly right-wing and upper middle-class, while The Daily Mail and The Daily Express were the middle ground between the “respectable” newspapers and the popular “red tops” (The Mirror, The Sun). The down-market papers were full of scandal, sensational crime stories, strip cartoons and pinup pictures of busty young women, wearing bathing suits and sometimes less.

The Evening Press, like more than a hundred similar “afternoon” newspapers all over Britain, ran mere updates on national and international stories, presuming their readers would have read the national papers over breakfast. But what built newspapers like The Evening Press was the blanket coverage of local news — and the horse racing results, which were updated in no less than five editions every afternoon.

At the time, newspapers were heavily unionized. There was a union for the editors (the Institute of Journalists), one for the reporters (the National Union of Journalists) and half a dozen others covering typesetters, the men who ran the printing presses, delivery drivers and sundry other trades.

On my first day, I was issued my National Union of Journalists membership card, a small hard-covered booklet which opened to a passport photograph of myself and the bold-face capital letters: PRESS. At the back, there were blank pages to be completed and checked off week-by-week by the head of the union branch (known as the Father of the Chapel) when I paid my union dues every Friday. Smart policemen, checking press credentials at a crime scene, would turn to the back pages of the card — and refuse co-operation unless you were fully paid up. After all, they were in a union too…

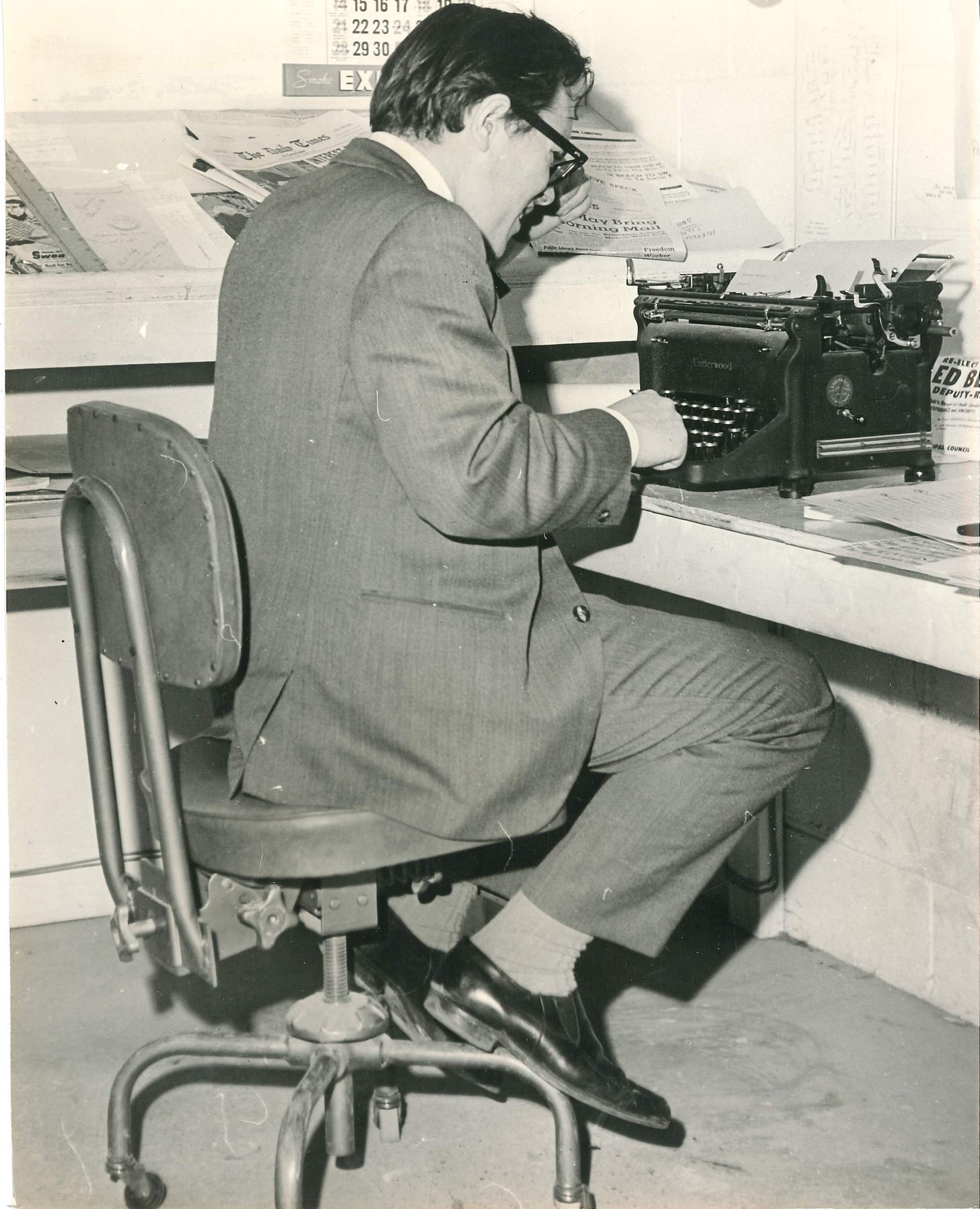

Life in the reporters’ room

There were eight or nine reporters on staff at the paper, and each morning most of us would arrive for work by nine o’clock. The reporters’ room had half a dozen steel tables, solidly built Underwood typewriters and a huge clock on the wall to remind us that deadlines were deadlines, and could not be missed. Each day began with a meeting when the chief reporter — consulting a giant journal known as “The Diary,” which listed every upcoming event in the city — who would give us our assignments for the day.

Stacey Brewer gets to review the new play at the York Repertory Theatre, the lone woman on staff (who was secretly writing Mills & Boon romance novels between assignments) is to cover the Women’s Institute convention, Ted Raine will cover the court, and Flohil will do the daily shopping report, and then back up the court reporter.

The junior reporters — myself and a puffy boy called Mike Hatfield, who I didn’t think was very bright but grew up to be the well-respected labour reporter at The Times in London — were assigned the menial tasks. The shopping notes was my weekly job for at least six months; Mike and I also did “calls,” which involved walking to the central police station to look at “the book” that listed the previous night’s crimes, accidents, and arrests.

After that, we would return to the office, and begin phoning every hospital and ambulance station in the area. “Hello, Evening Press here. Anything doing? All quiet then? Thank you…” Once in a blue moon, we would pick up the kernel of a story, but mostly it seemed a pointless exercise. Unlike reporters today, who routinely tune in to police and fire department radio calls, that was out of the question in Britain in the ’50s: a serious breach of the punitive Official Secrets Act.

In the coming months, I covered council meetings and courts, soccer and cricket, exhibits at the art gallery, ribbon-cutting ceremonies at the opening of new shops, speeches by visiting dignitaries and meetings of the York Theosophical Society. I interviewed criminals and policemen, actors and archbishops, transvestites and tourists, local councillors and visiting Members of Parliament, strippers and drag queens. Every working day was unpredictable and always different.

I was sent to the home of a widow who had just learned that her husband had been run over by a bus. I was assigned to obtain a photograph of the accident victim, a rite of passage for all newspaper reporters. There’s nothing quite as difficult as this, and I remember hesitating on the corner of a street of back-to-back row houses, plucking up my nerve.

“Mrs. Figgins? I’m from The Evening Press, and I’m sorry to intrude at this time, but I wonder if you have a picture of your husband that we could print in the paper … I’ll make sure you get it back…”

“Come in, lad! My Fred’s picture’s going to be in t’paper? My goodness, that’s lovely.” She took down a photograph from the mantel and handed it to me. “That’s Fred,” she said. “’e were a grand feller; I’m going to miss ’im… Would y’like a cuppa tea?”

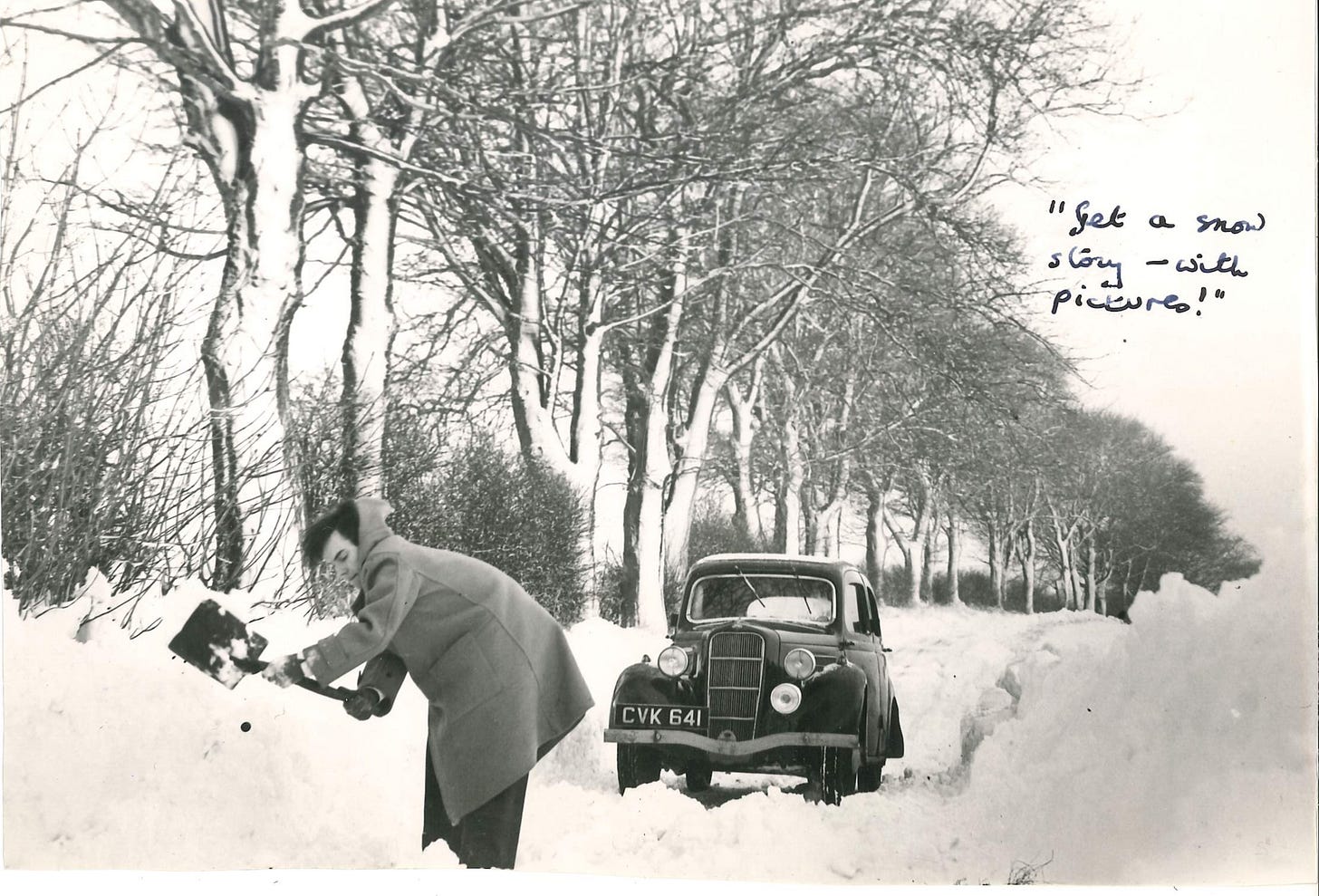

A standby for a slow news day

On a slow news day, there was always a standby: a story about the weather. Half an inch of snow, two days of rain, a minor flood in a nearby village, a chimney struck by lightning? Off you went with a photographer to get a picture of the snow, or the waterlogged street, or the fallen chimney. On a really slow day, that could be front-page news.

A quick primer here for folk who want to know how newspapers “worked” back then.

Reporters wrote their copy on sturdy typewriters, using paper with two carbons; you kept one, the chief reporter kept one, and the top copy went to the subeditors, working a huge round table in another room,

At The Yorkshire Evening Press, the “chief sub” was a grumpy Scot called Stuart Mackie, who was feared by everyone on the paper. He’d glance at your copy, and send it back to you for a rewrite if he didn’t think it was good enough. If the copy passed that test, he marked the first page with a code that told the subeditors sitting with him at the table how many lines the headline should have, and what type size and style should be used.

They then checked the copy, wrote the headline, and put it in a basket in the middle of the table. Every 20 minutes or so a copy “boy” (usually an old-age pensioner) would take it, stuff it in a pneumatic tube, and it would whoosh off down to the composing room, where two dozen Linotype machines clanked away, setting the copy into hot lead type.

One of the subs was Maurice Moyes, a tall but stooped man who had never been quite the same after being struck by an ambulance as he cycled to work. Maurice was an avid reader of The New York Times — surely a rarity in England at the time. He loved that newspaper’s tight headlines, usually set over a single column, which used short words like “hint,” “bid,” “probe” and “peep.” Brevity was important to Maurice.

Given a story about a local town council that was changing its mind about what to do with some land it owned, I wrote a forgettable headline, threw the copy in the basket, and went on with my work. Maurice, however, when nobody was watching, retrieved my copy and wrote an incomprehensible new headline: “Dilly Dally Policy on Plot Site Call.” It earned me a severe tongue-lashing from the chief sub. “You could set that bloody tripe to music!” he shouted, before he figured out what had happened.

Everybody has a story; you just have to find it

At £3 a week, life was financially impossible, especially since I now liked a drink in the pub at day’s end, smoked incessantly and was dating a pretty young girl I’d met in typing class. There was precious little time — as well as very little money — to do anything but work, cycle home 12 miles (often very late at night), cycle back to work the next morning, and keep going.

My saving grace was a daily column in the paper called A Yorkshireman’s Diary, full of three or four paragraph items of observations, overheard conversations, and leftover remnants from news stories. For every item you submitted that made the column, you earned another two shillings and sixpence. So I wrote about eccentric shopkeepers, visiting pop groups, rural villages with odd names, a joke the Archbishop of York had made at a reception, witticisms made in court by be-wigged and red-robed judges, and hundreds of other “soft” subjects.

I believed (and still do) that there’s a story behind every business, every event and every person — all you had to do was find it, see it, hear it and write it up. That way, I could double my weekly salary, and spend the extra money on cigarettes and warm beer.

(Part 2 of these reminiscences will follow in a couple of weeks…

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

SUBSTACKS I’M FOLLOWING THAT YOU SHOULD DISCOVER

— . Commentary on music he enjoys, and a great source of music you’ve not heard. Plus invaluable listings of live music shows in Toronto and on the road. — . One of the very best singers out there writes a thoughtful and funny Substack that’s always worth reading.. An award-winning Canadian novelist, Terry has written half a dozen successful books that are both funny and pertinent. His Substack offers excellent writing about writing. — . True tales about the early days of Canadian country music, often related to the life and music of Stompin’ Tom Connors. — . There isn’t a music-oriented Substack with an audience even a quarter as large as Ted’s. Ridiculously prolific, there’s not enough time to read all his posts, but one out of every three or four of them will change the way you listen and think and talk about music.Five more recommendations next time around!

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

VIDEO LINKS FOR YOUR WEEKEND

Two videos from my dear friend Loryn Taggart, who is playing NXNE in Toronto June 13 (Free Times Café, 11 p.m.), the Ottawa Blues Festival (July 4, 8 p.m. on the River Stage) and all three days of the Mariposa Folk Festival in Orillia (July 5-7).

She’s also singing as part of my 90th birthday concert at Lula Lounge on June 24 — getcha tickets now!

Here’s her latest video, recorded and filmed in Montreal six months ago — intense, tuneful, and distinctly Loryn:

And here’s Loryn’s very first video, from 2010. Rough and ready and not well filmed, but you can see and feel the woman’s raw talent. It was the first video of hers I saw, and I’ve been a fan and friend ever since.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

A FINAL WORD (OR TWO)

Been telling true stories (mostly directly about music) for nine months now. Tried putting stuff behind a paywall for a couple of weeks, hoping to gain additional paid subscribers — but it didn’t seem to work, and it’ll be a while before (or even if) I try it again. So, if you’re enjoying these stories, the best way to keep ’em coming — and supporting the work that goes into them — is to upgrade to paid. $6 bucks a month won’t break your bank, I sincerely hope. But however you subscribe, I appreciate your readership.

Next time: Three terrific artists who quit, and why … and five more Substack recommendations.

When I was a tv producer, I always told reporters the same thing: Everybody has a story worth telling, you just have to talk to them for a few minutes to find it.

This was fascinating! Thank you for sharing your Substack recommendations as well, you've given me some cool people to follow :)