Stories from the Edge of Music #32: Sleepy John Estes brings the blues to Canada

And meet the man who helped change pop in the '60s

Still reeling from a streaming “summer” head cold, this is the second time these stories have been delayed. Antibiotics are starting to work their magic, and regular service will be resumed shortly! Thanks to all the new subscribers — some 30 each month — with the hope that some of you will become PAID subscribers. Whether or not you’re a paid subscriber, you’re more than welcome here!

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Rare footage of Sleepy John Estes with Yank Rachell on mandolin

NOT THE WAY TO LAUNCH A CONCERT PRODUCTION CAREER — BUT IT WORKED

Sleepy John Estes—gaunt, blind, old and gap-toothed—was the artist at the first concert I ever promoted. It was a strange beginning to a concert promotion “career” that later included shows with such varied artists as Muddy Waters, Irish band the Chieftains, Miles Davis, blues stars B.B. King and Bobby Bland, Canadian trumpet virtuoso Maynard Ferguson and the reclusive Leon Redbone, among many others.

This was 1962, and I didn’t have even the vaguest idea of what I was doing. And nor did my collaborator, an eccentric doctor called Beverley Lewis.

With his accompanists, Yank Rachell and Hammie Nixon, Estes drove from Chicago to Toronto. And once they had settled into their hotel, we faced the first unexpected piece of business — Estes had left his white cane at home, and needed another one. This involved driving him to the Canadian National Institute for the Blind. Staff there, once they realized that he was indeed sightless, gave him a new cane.

And then we organized a press conference for him.

His musicians, mandolin player Rachell and harmonica ace Nixon, sat on either side of him, and three or four media people asked questions. One of them, noticing that Estes was nodding off, holding on to his cane, asked: “Why do people call you Sleepy John?”

Rachell nudged him, and he straightened up in his seat. He mumbled something, but his accent rendered his answer almost meaningless. Blind, old, gaunt — and narcoleptic.

A meeting with a legend

For me, this was a meeting with a legend. My motive in presenting him to a Toronto audience was totally selfish: I wanted to meet him hear him, and share my “discovery” with others.

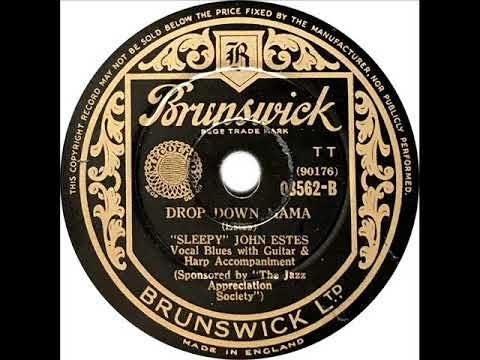

He was, after all, the voice on the first blues record I had ever bought, at the age of 16. The 78 rpm record, on the Brunswick label, featured two songs: “Drop Down Mama” and “Deep South Blues.” It was one of the very first blues records released in Britain — and it made a lasting impression.

Recorded in 1935, it was different from anything else I had ever heard. Keening and emotional, with Estes’ strangled voice and the mandolin accompaniment (rare indeed in the blues), I could hardly understand the words but the sound was instantly appealing.

Despite his age, his blindness and his narcolepsy, Estes was — despite his abject poverty — one of the most significant figures in the history of the blues. Raised and living in Brownsville, a small town in western Tennessee, the songs he recorded in the late ’20s through to the ’40s were unusual. Unlike many rural blues singers — most of them from Mississippi — Estes’ songs were about his family, friends, neighbours and events in his community.

He was, in fact, a folk singer — what other blues artists wrote and sang songs about the local attorney? “Lawyer Clark” was the only man who could prove that water ran upstream. And “Floating Bridge,” a song about a near-drowning experience. Who else made songs about the minutiae of small town Black life in a now-distant era?

After making his last records in the early ’40s, he was rediscovered a few years later, and Bob Koester’s pioneering Delmark record label released a series of albums of new songs, beginning with The Legend of Sleepy John Estes, which included a stunning song of unrelieved poverty, “Rats in My Kitchen.” Playing that record again, decades later, one is still struck by the power and starkness of the songs and the performance.

Bringing the blues to Canada

Following my first visit to Chicago, it seemed logical to bring blues artists to Canada. The idea that one could actually make money presenting blues people in the uptight atmosphere of Toronto in the early ’60s seemed irrelevant; if one could just cover the costs, that would be enough.

Through my Chicago friend Bob Koester and with the invaluable help and encouragement of Beverley Lewis, we made arrangements to bring Sleepy John Estes to Canada for the first time.

Beverley had figured out how we would make this all work. We would hold the concert for two nights at the First Floor Club, an unlicensed jazz club in a basement of a house close to Bloor and Yonge Streets, then (as now) at the geographic centre of downtown Toronto. The venue held some 50 people.

We would pay Estes and his accompanists $300, and raise the money by selling advance tickets for $10 to about 50 of our friends; that was an expensive ticket back then.

If we made any income at the door, we would pay everyone back — and at the final reckoning of the two sold-out shows, all our initial subscribers got $9.50 back. We had broken even.

It was then, too late, that I remembered I had not paid for the wonderful poster designed by Willem Hart. When I covered his modest bill, I realized that I had lost money at my very first concert promotion.

A city’s music scene in the early ’60s

The reality, however, was that blues artists were already coming to Toronto as entertainers to work in bars and clubs that dotted downtown. Jimmy Reed, an iconic figure whose hits included “Big Boss Man,” played a series of shopping centres in suburban Toronto. An epileptic, he had a seizure at one of them, but Beverley, who was present, helped get him back on his feet.

The more “upscale” clubs — such as the Colonial, the Brown Derby, the Edison, the Town Tavern, the Zanzibar and Le Coq d’Or — were on Yonge Street, the city’s main drag. And all of them featured American jazz artists and Canadian show bands.

In the rougher joints on Jarvis Street — the closest thing to a tenderloin area that the city’s fathers could tolerate back then — Black artists dominated. They felt welcome in a city that was relatively tolerant; they were unlikely to be refused service at restaurants and bars, and were not turned away at hotels because of their colour.

At the Westover, Warwick, and Westmoreland hotels, the atmosphere was loose. Hookers and their pimps were at ease; outsiders got eyeballed, evaluated, usually accepted, and often laid in the upstairs rooms that were rented by the hour. The music was loud and raunchy.

There’s hardly any live footage of Jackie Shane — this rare clip was from a Nashville TV show, Night Train

At the Warwick — now a strip club called Filmores and soon to be razed for another condo building — and at the Sapphire, Little Jackie Shane blurred gender lines and screamed rhythm and blues with all the power and passion of their namesake, Jackie Wilson. Raunchy comedians hosted the revels with ribald putdowns in the style of the Black comics of the time, Moms Mabley and Redd Foxx.

And Brandy, a giant transvestite, was the star attraction, along with a band led by Frank Motley who delivered a deep-in-the-bucket soul revue; the leader’s most noticeable talent was his ability to play two trumpets simultaneously.

But Beverley and I were less interested, then, in Black music as “entertainment.” Naively, we wanted to bring blues to a more upscale audience — serious music fans like ourselves. And, apparently, we had given ourselves a mission.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

MUSIC BOOKS FOR YOUR LIBRARY: MEET JOE BOYD, PINK FLOYD’S FIRST PRODUCER

I first met Joe Boyd when, in his early twenties, he was road managing the American Blues and Gospel Caravan with Muddy Waters, Sister Rosetta Tharpe and Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, among others.

Now, for the first time in 15 years, I’m re-reading his 2006 book White Bicycles: Making Music in the 1960s. And the front cover blurb, from Brian Eno (of all people) is accurate: “The best book about music I have read in years.”

Boyd, an American who seems more English than most Englishmen, was a pivotal figure in the underground music scene of the day. He ran the British office of Elektra Records, and helped run sound at the Newport Folk Festival when Dylan “went electric.” He formed his own label and produced so many seminal artists — Fairport Convention, Nick Drake, Mary Margaret O’Hara, the Incredible String Band, Maria Muldaur, the first album by 10,000 Maniacs among them. Oh, yes, and he produced Pink Floyd’s first single.

He writes about all this with grace and charm and a healthy sense of self-deprecating humour. The book is hard to find, though Amazon and Abe Books can probably unearth one for you. The copy I’m reading, autographed, was gifted to me by my friend Karen Pace — it now has a permanent place in my library.

PS: A few years ago, when the Luminato Festival was a prominent part of Toronto’s cultural scene, I was invited to interview Boyd on an outdoor stage before some 400 people. Afterwards, I wrote him an effusive email about how excellent he had been. His response, which I’ll always cherish, was simple: “It takes two to tango. You danced well.”

This is a lengthy video interview with Joe Boyd — but anyone even slightly interested in the music of Pink Floyd will be fascinated by his insight and his stories.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

AND NEXT TIME...

…A personal piece about my youthful days as a boy newspaper reporter. There’ll also be more music stories! And the week after that, adventures with Muddy Waters, the most solemn and dignified of men.