I know what you’re thinking: “Folk” festivals are hippie-dippy kumbaya events, complete with peace, love, and buxom girls wearing paisley dresses and Birkenstocks, helicopter-dancing by the side of the stage. What’s the very opposite of “cool”?

So, welcome to the 9th edition of Richard Flohil’s Stories from the Edge of Music. Flohil’s been to well over 200 “folk” festivals and survived —this’ll be the first of several editions about this part of the music world over the next month or two. Many tall tales, and some laughter guaranteed.

If you haven’t subscribed yet, you might think of doing so. There’s a lot of fun (and a smidgen of real information and/or inspiration) in these pages, and he’d love to have you along for the ride. So far, almost 350 people seem to be enjoying these missives…

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

What the folk? Amazingly, folk festivals are now a major part of the music landscpe

The four major folk festivals in Canada — held in Winnipeg, Calgary, Edmonton and Orillia (two hours north of Toronto) — may be the largest, but there are dozens of smaller events across the country. Each of them (and there are some 25 in Ontario alone) make massive cultural and economic contributions to the communities of which they are part.

Early Canadian festivals pioneered a basic pattern, and there are now countless similar events in the United States, the U.K., Australia and New Zealand.

Run with a handful of permanent staff members and hundreds of volunteers, these festivals play a major role in the development of new talent. The folk who choose the performers and programme festivals — known as “artistic directors — are among the most important gatekeepers in the entire music business.

How to get on their radar, and how to get chosen, is the subject of another edition of Stories from the Edge of Music in the near future.

But before we get there, some personal history...

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

My first festival, and my first music mentor

When writers tell you they don’t know where to start, they have to shake themselves, pull up their pants, and begin — at the beginning.

OK then. It’s 1965 and I have accidentally acquired a reputation as a blues ”expert,” thanks to fact that, with a friend, I have presented a handful of Chicago-based performers to Toronto audiences. The artists all had odd names: Sleepy John Estes, Muddy Waters, Robert Nighthawk… and they all made superb music.

A pleasant woman called Estelle Klein phoned me: Would I come to a folk festival in rural Ontario and host something called a “blues workshop”? Not knowing what a folk festival was, or what on earth a “workshop” could be, I accepted.

The first Mariposa I went to, in August that year, was at Innis Lake, north of Toronto. Estelle, the artistic director, had chosen a lineup of artists who, in future years, would seriously strain most festivals’ budgets: Ian & Sylvia, Gordon Lightfoot, Phil Ochs, John Hammond, Leonard Cohen and a young girl from Saskatchewan called Joni Anderson.

And the blues workshop I hosted included Hammond, guitarist Amos Garrett and the legendary Son House, the pioneering Delta guitarist who had mentored Robert Johnson back in the early ’30s. My co-host was a tall, lanky Bostonian called Dick Waterman, who managed Mr. House (as he always called the elderly musician). Sadly I remember the pair of us sitting around a picnic table with the singers — while they performed, he and I scanned the audience for pretty girls, muttering overtly sexist comments that we are rightly ashamed of today.

The festival was attended, maybe, by 2,000 people, but the police presence (20 or 30 Ontario Provincial Police motorcycle cops in full gear) indicated they expected a serious drug-fuelled hippie riot of some sort or other.

However, there were no riots, no arrests, no beer garden, no marijuana, and no backstage parties — unless coffee-and sandwich gatherings sponsored by a local women’s church group could be described as post-show bacchanalia.

A year later, the lineup included return appearances by Ian Tyson (who hosted two evening concerts), Lightfoot, and Joni Anderson (before she became Joni Mitchell), the Staple Singers, Doc Watson, Tom Paxton, Pete Seeger, the New Lost City Ramblers and the Rev. Gary Davis.

The blues workshop included Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, classic black vaudeville singer Sippie Wallace and (so says the programme, but I can’t remember them at all) Chicago blues players Sunnyland Slim, Johnny Young and Big Walter Horton. Once again, my co-host was Dick Waterman — and, all these years later, he and I are still friends.

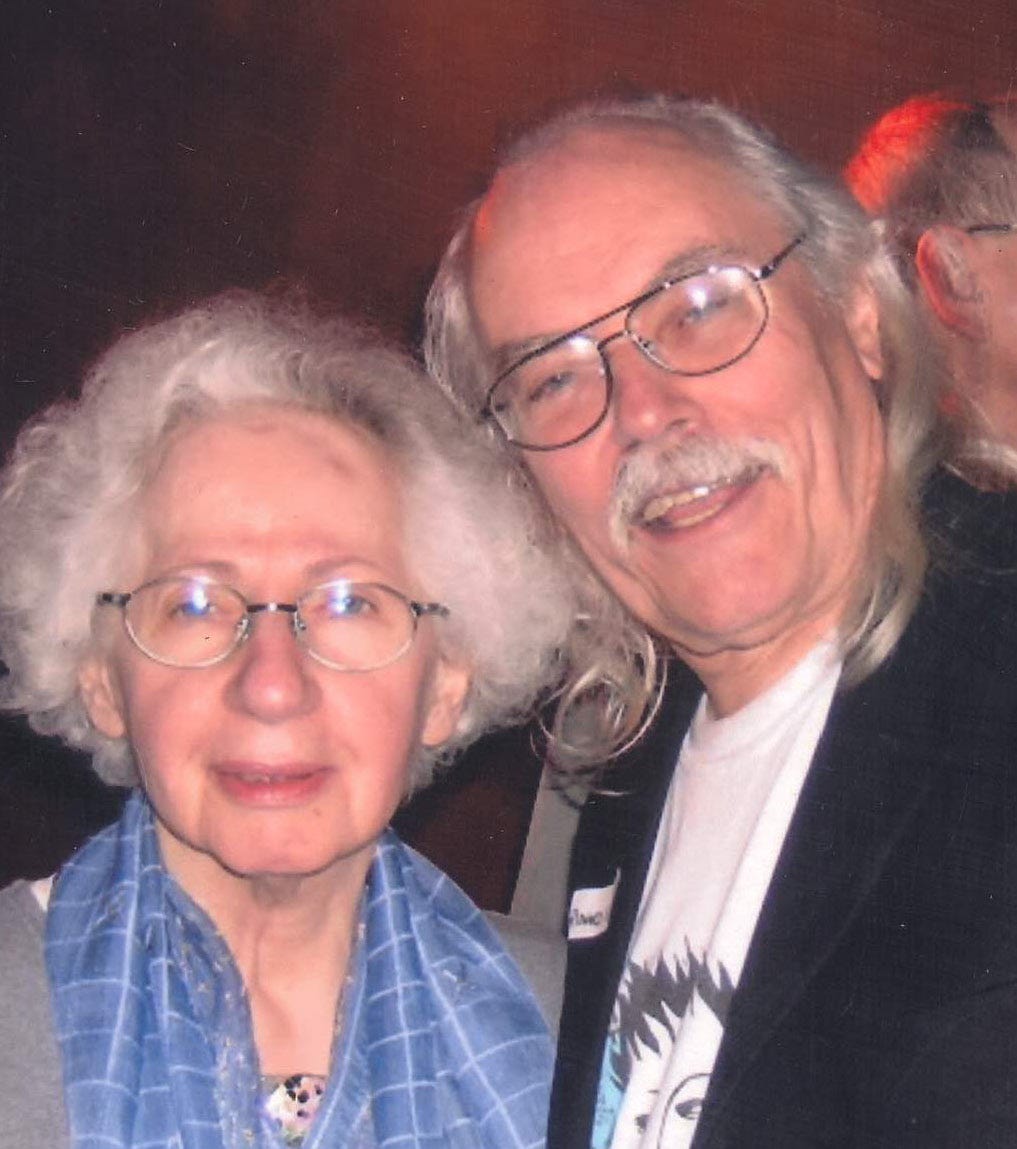

And I really got to know Estelle, the diminutive white-haired woman who was the artistic director of the festival. She became my first music mentor.

Estelle set the pattern that folk festivals in Canada still follow today, half a century later.

Concurrent “workshops” were programmed on three or four different stages during the day; evening concerts offered solo sets by five or six artists or bands.

The workshops are her best legacy. The idea, simply, was to present specific themes or subject matters that artists were expected to follow — train songs, for instance, or love songs or political songs, or songs of alienation. Artists, who sometimes had not even met each other before, came together to share songs. Sometimes it was magic and sometimes a train wreck — but always worth watching and listening.

Estelle would make the rounds of the various stages, partly to hear the music, and partly to remind the artists — via pencilled notes — to stick to the topics she had set.

At home in Rosedale, an affluent area of Toronto close to downtown, she and her husband Jack — a prominent architect — held frequent salons, hosting artists as varied as Bob Dylan, Leonard Cohen, Pete Seeger and Donnie White, the young son of the singer Josh White. Other regulars in the Klein’s comfortable living room included the leading lights of Toronto’s folk scene of the sixties: Lightfoot, Bonnie Dobson and Owen McBride among them.

At Estelle’s suggestion, I offered to handle publicity for the festival after the 1965 event, and thus began a long on-and-off relationship with Mariposa that still exists today. I’m proud to be a member of the festival’s Hall of Fame.

P.S.: Today, after six decades, Mariposa is one of the most successful festivals (of any genre) in Canada. It’s held in Orillia, north of Toronto, and for the last three years has sold out in advance. And, yes, there is a workshop stage named in honour of Estelle…

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

THE DANGERS OF DRINK AT A DRY FESTIVAL

In 1966, the Mariposa Folk Festival was drier than a temperance preacher’s bedside table. The demon drink was even more feared than pot, which was hardly a factor at that time.

Sometime during the second day of the festival, Pops Staples, the patriarch of his family’s gospel group, asked whether I could get him some whiskey. After a quick 20-minute run to the nearest liquor store, I smuggled in a fifth of Canadian Club and quietly handed it to Staples, and thought no more about it.

That evening the show was opened by the Rev. Gary Davis, a blind, morose man who had earned his reputation as a powerful guitarist, and who wrote songs popularized by the leading commercial folk artists of the day, including Peter, Paul and Mary.

However, Davis was obviously drunk. Teetering on his chair at the edge of the stage, he slurred his words, forgot his chord changes, and made salacious remarks to and about a group of young women in the front row of the audience. After a few minutes, Estelle Klein and Dick Waterman quietly walked him off stage.

At the coffee gathering after the show, Pops Staples winked at me, and said: “I see the Reverend was a little under the weather tonight. But you and I won’t tell Miss Estelle where he got his drink from, will we?”

“You mean, the whiskey I got for you…?” I asked. Staples, one of the most dignified of men, merely inclined his head and smiled.

The next evening, Davis returned to the main stage and delivered a faultless set of blues and gospel material, totally redeeming his previous dismal performance. And Waterman, familiar with the task of shepherding old bluesmen through a strange white world, changed his airline tickets and safely took the Reverend back to his New York home.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

QUOTE OF THE WEEK

“Discover OLD music. It will be brand NEW to you.”

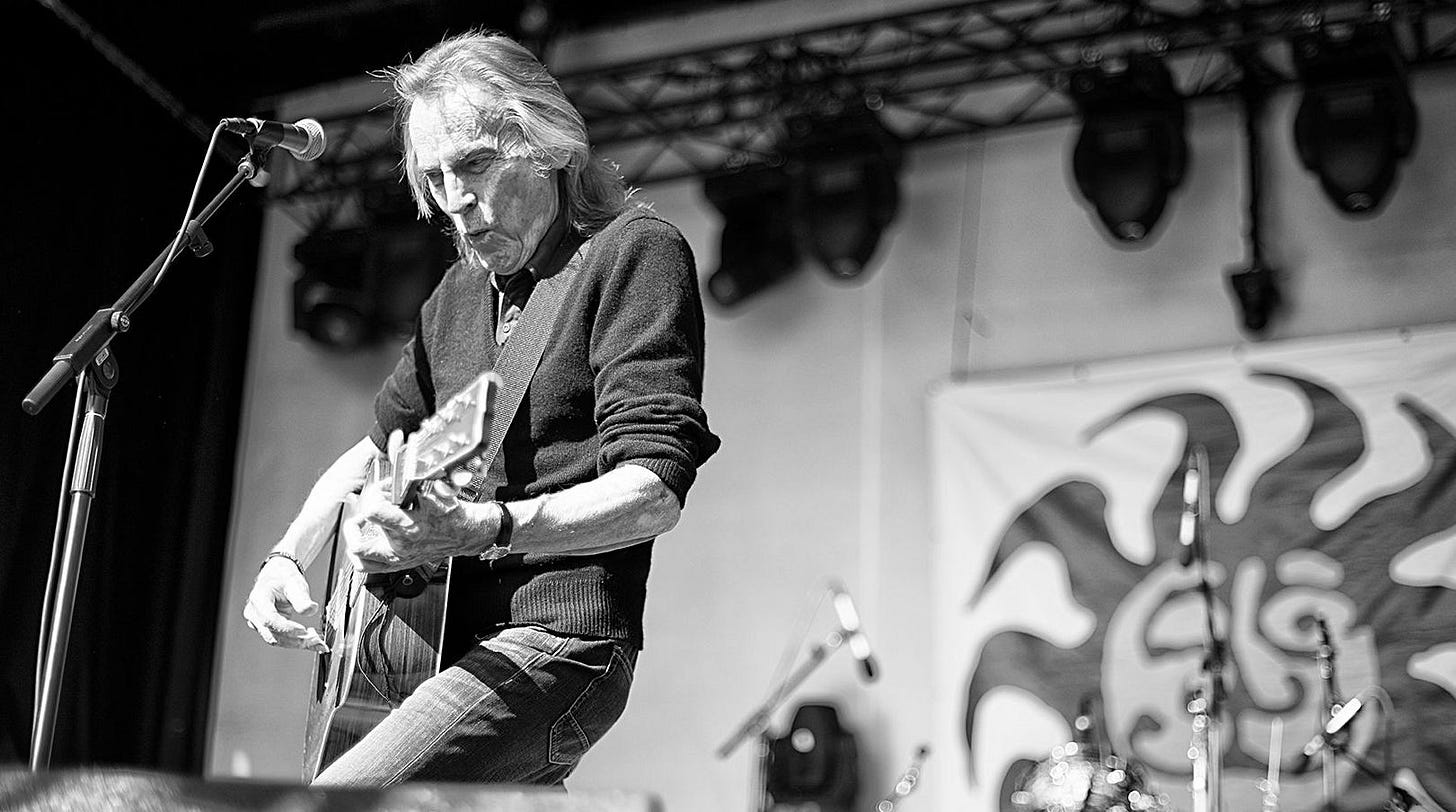

— Ken Whiteley, the godfather of the Toronto folk music scene

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

VIDEO LINK OF THE WEEK

Please check this — the greatest of the rocking gospel groups, featuring Pops Staples and his incandescent youngest daughter, Mavis. We shall not see a band like this again, but Mavis — now in her eighties — continues the tradition and continues to tour as a solo artist, backed by a superb small band.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

AND NEXT WEEK…

A fabulous story about the late Rolling Stones drummer Charlie Watts — from the days when he needed a tax loss and when the CBC had more money than it knew what to do with….

Tom — so happy you are here! Hope you can access some of the previous stuff — you might smile at the KD Lang stories. And next week's Charlie Watts story, as a CBC person, will definiely make you laugh.

I was there and still remembering rev Gary repeatedly bumping the mic with his guitar and finally realizing it wasn’t just that he couldn’t see it - he was smashed. And now I know who was responsible!