#7 Stories from the Edge of Music: Miles Davis

The jazz genius tried to buy my car, + meet'n'greets & more

Here’s the seventh instalment of a weekly collection of true stories and warm-hearted memories by a publicist and concert promoter who spent more than 50 years in the music business.

Unable to sing, play an instrument or even dance, Richard Flohil is passionate about music.

Based in Toronto, now the fourth largest city in North America, he hopes you’ll find these stories worth your time — and even a $6.00 monthly subscription (or a discounted annual sub). That’ll keep the stories coming and top up his old age pension.

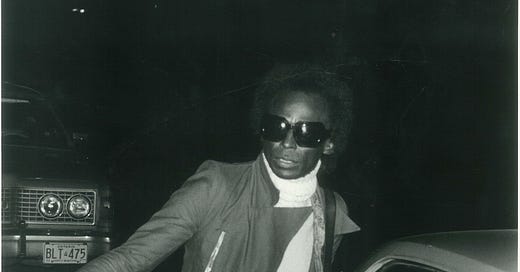

THE NIGHT MILES DAVIS TRIED TO BUY MY CAR

More than 50 years later, it’s hard to remember just how I wound up as the promoter of a concert with the reclusive, eccentric, ground-breaking jazz trumpet player Miles Davis.

But in January 1974, I am standing onstage at Massey Hall, the legendary Toronto concert venue. The star of the show is 45 minutes late. The sold-out audience is getting restless, and the manager of the hall, the amiable Joe Cartan, is nervous. The musicians are ready, but the star of the show has not turned up.

I have to go on stage and tell the audience something, anything, to assure them that the concert is going to happen. “Miles Davis is on his way,” I say. “Good things always happen to those who wait, and…” I glanced down, and noticed to my dismay that the seam on the left sleeve of my suit jacket had somehow come undone; the sleeve could fall off at any moment.

My simple speech fell apart, and I stumbled into the wings — at the same time, Davis came through the stage door, handed me his overcoat, took his trumpet out of its case, and walked on stage to an instantaneous ovation. Cartan and I walked to his office, and he opened a bottle of Scotch.

The show itself is something of a blur. I spent most of it figuring out the expenses and preparing the final settlement with the hall and with the artist’s road manager. Standing beside the stage for the second half, I watched the band play highly improvised “free” jazz, marvelling at the size of the amps, all decorated in Jamaica’s green, black and gold national colours — and surprised by the sheer volume of the performance.

The reviews the following day were mixed. Jack Batten, writing in The Globe and Mail, said Davis offered “music that was almost as disturbing — in a different, more challenging way — as the delay.” With no less than three percussionists in the six-piece band, the music, he said, was a “kind of replacement for traditional harmonies, since the soloists didn’t follow any of the usual jazz chord changes.” Sax player Dave Leibman played long, soaring wailing solos, while Davis was “cranky and eccentric,” he added.

Peter Goddard, in the Toronto Star, pointed out that the audience tolerated Davis’ aloof poise and on-stage arrogance, adding “(the) edgy feeling, more than his late starts, is what keeps his audience coming back for more.” And one member of the audience, writing on Facebook years later, remembered leaving the hall 20 minutes after the concert had started, giving his ticket to a fan who couldn’t get in. “You’ll hate it,” he said.

The show closed with a 24-minute piece that ended with a 10-minute conga solo and a 45-second coda. Davis walked off, barely acknowledging the applause. He did not return for either an encore or a bow.

With his coat slung over his shoulders and a bottle of beer in his band, Davis waited inside the stage door for the limousine. When it didn’t arrive, I offered him a ride to his hotel; he took a slug of beer and got into my rusty Toyota.

How do you tell a brooding, nearly silent jazz star that drinking beer in a moving car is against just about every rule in the book in Canada? I simply prayed that no police officer would see us on the brief ride to the hotel.

“So,” he croaked as I pulled away from the sidewalk, “what’s this car worth?” Surprised, I told him that I had had an equally beaten up vehicle, traded it in and paid $2,000 for this one.

“If I give you $2,000 in cash, can I buy it?” he asked. “I wanna go home.” Before I could properly explain how impossible that would be, given import licences on vehicles crossing into the United States, and how I really didn’t want to sell the car anyway, we arrived at the hotel.

He got out, managed a weak smile, and walked into the lobby.

The next day, Mike Watson, the promotion rep from his label, Columbia Records, picked up Davis and drove him, in near silence, to the airport. He was to fly to Montreal, where he had a sold-out concert at Place des Arts, promoted by Donald K. Donald — at that time the most powerful impresario in the country.

Davis never showed up. Watson fielded a number of anxious calls from Montreal: where was Davis? “I put him on the plane,” he said. In fact, unknown to Watson, Davis changed his ticket and — as he had thought he could in my car — found his way home to New York.

It took me almost 40 years to discover what had happened. Don Tarlton — Donald K. Donald’s real name — remembered the aborted show quite clearly.

Apparently, Davis had previously played in Montreal for another promoter, and there had been a financial dispute. In retaliation, a lien was placed on the band’s gear on the next occasion Davis played in the city. Given the fact that the show was on a Sunday, nobody at Place des Arts knew what to do and a legal solution seemed out of the question in the time available; Tarlton cancelled the show and went home.

It would be some years before Miles Davis would return to Canada.

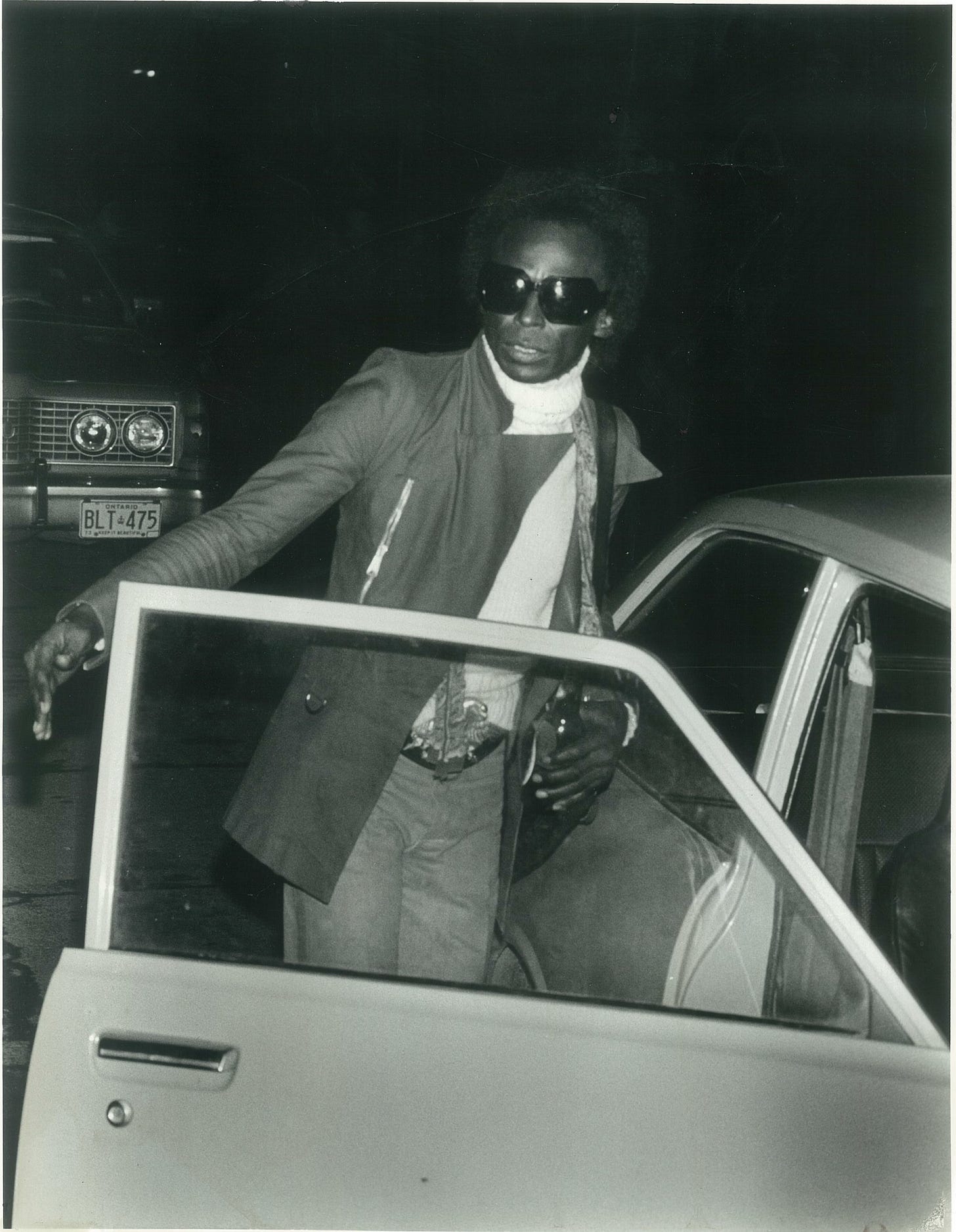

In 1983, Rob Bennett and I jointly promoted another event with Davis, this time at the 3,200-seat O’Keefe Centre (currently renamed Meridian Hall). Once again, the house was sold out, and Davis was as silent and brooding as he had been at Massey Hall.

On stage, he was a little more energetic. His crew had laid out fine white lines on the top of the amps. He refreshed himself during the show. Davis refused to play the material that he built his career on — Kinda Blue, Sketches of Spain — in favour of funk and experimental free jazz, influenced by artists such as Jimi Hendrix and James Brown.

As he left the stage, his manager stood in the wings, holding two loaded coke spoons.

Backstage, however, he was with his wife, actress Cicely Tyson, who was as cheerful, chatty and ebullient as her husband was withdrawn. She swanned into the green room, prior to the show, trailing $20,000-worth of white fur coat on the floor behind her, introducing herself to everyone in sight with a radiant smile and hugs and kisses.

This time, the limousine did turn up and he didn’t need to try to buy my car.

When Miles Davis died in 1991 after a stroke and a bout of pneumonia, the world lost one of the most influential jazz artists in history. Difficult, silent, seemingly always angry, his music was a perfect reflection of his personality.

Spending even a day with the man gave me memories and stories to last a lifetime.

BACKSTAGE STORIES WITH BONNIE RAITT, B.B. KING, BUDDY GUY AND DOLLY PARTON

I wish I could remember where on the web I stole this from, but it’s priceless. A couple approached a music celebrity on the street (maybe Robert Plant?) and asked “May we take you picture?”

The celebrity’s response: “Of course. That’s my job.”

Most photos with celebrities happen backstage — and backstage meet’n’greets vary from artist to artist. On her recent tour, Bonnie Raitt limited her guest list to close friends, and made us all take COVID tests before meeting us. Who can blame her? A bout with the plague could derail a whole tour.

Loreena McKennitt, usually the most gregarious of post-show hosts, suspended backstage visits altogether.

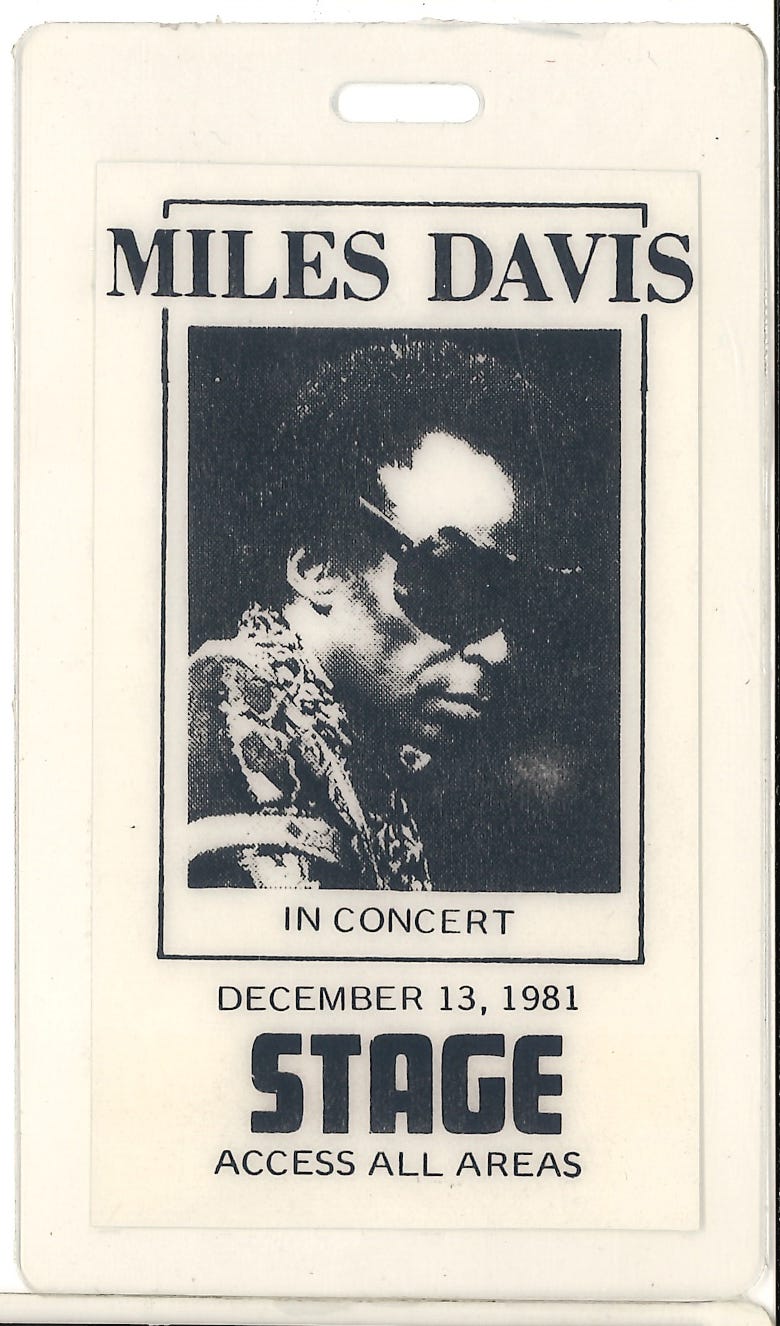

A few years ago at Toronto’s Massey Hall, B.B. King entertained the opening band in his dressing room with drinks and food after the show. The Downchild Blues Band members swapped stories with the star, took pictures and got autographs. When they left, there was line-up of people outside the star dressing room, including the mayor, the president of Guy’s record company, the general manager of the hall, local jazz radio folk, and a couple of music writers. They all had to wait while the star spent time with the opening band. B.B. King was always a class act.

Buddy Guy meets people before the show — because he closes his set with a screaming guitar solo, walks off stage, hands his guitar to a crew member, climbs in a limousine and leaves the building. While the audience is still screaming for an encore, he’s sitting in his hotel suite eating his post-show dinner, served promptly at 11 p.m.

Dolly Parton, too, hosts her VIP guests before her performance. Before you meet her, you’re requested not to ask for autographs, and not to take pictures. Instead, her crew take the photographs as you exchange pleasantries with the star; three days later you can go to a specific website and download your picture.

Incidentally, Ms. Parton was dressed to the nines, was utterly charming — and 20 minutes after we had all left, she hit stage wearing a totally different dress and an even more spectacular wig. I still can’t believe she dressed up specifically for the pre-show meet and greet!

These gathering can be exhausting for the artists. Back in the ’80s I met Canadian opera singer Maureen Forester, and I asked her how many recitals she gave each year. “Not as many as B.B. King,” she replied. “The recitals are lovely,” she added, “but it’s the post-show receptions that do you in.”

QUOTE OF THE WEEK

“The whole reason we write songs and sing them from the top of our lungs is to reconcile pain and beauty. Or at least give the effort and paradox some form of expression… That’s all I can say right now and it doesn’t feel like enough.”

— Canadian-Israeli singer-songwriter Orit Shimoni.

AND NOW, NEXT WEEK, SOMETHING COMPLETELY DIFFERENT

Are you ready for some stories about the marvellous Scottish comedian (and occasional banjo player), Billy Connolly? Here’s a taste: