#22 Stories from the Edge of Music: RUSH on the road — a flashback memory to 1980

… and 21 more things a publicist can do for a new artist

For six months now, Richard Flohil has been publishing stories here, usually every week or 10 days. They’re the memories of a man who’s spent 60 years as a writer, publicist, club talent booker, concert promoter, festival organizer and serious music fan (he’s been to 22 live music shows so far this year).

If you’d like to support his writing, consider taking out a PAID subscription. At $6 a month (less than the price of two Tim Hortons coffees and a donut) you get bonus material and access to all the previous Stories from the Edge of Music.

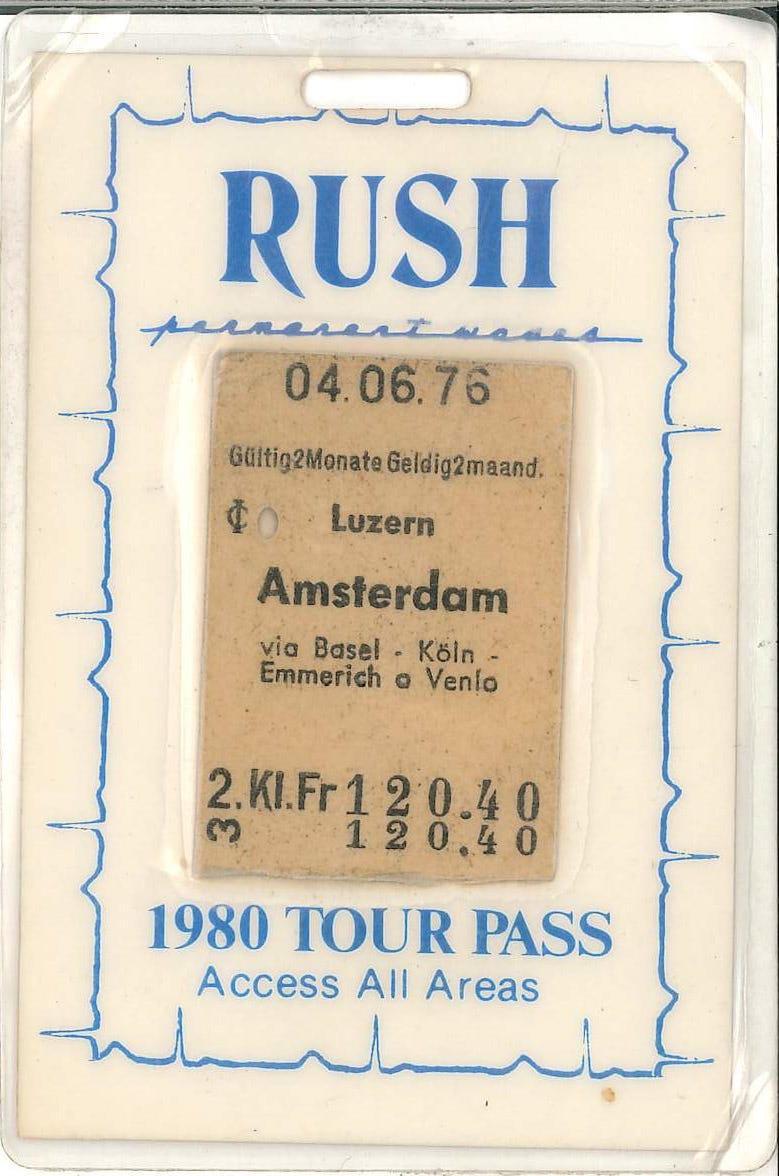

RUSH ON TOUR: A BACKSTAGE FLASHBACK

Apart from being one of the best-named bands in history, Rush was — in the days before Drake, The Weeknd and Justin Bieber — the biggest and brightest Canadian musical export.

By 1980, after years of slogging their way through the Toronto bar circuit, Rush was now playing arenas and outdoor venues across the United States to sold-out audiences.

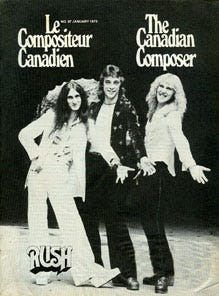

I had written about the band — Geddy Lee, Alex Lifeson and Neil Peart — five years earlier in The Canadian Composer, and so I suggested a story to an editor I knew at The Canadian, a weekly magazine that was distributed every Saturday with all the country’s major newspapers. My informal sales pitch was accepted promptly. Yes, I could go on the road with the band, write 1,200 words, and be paid $1 a word, plus my expenses. In 1980, that was a small fortune.

Which is why, in January that year, I was emerging from a taxi outside the Tingley Arena in Albuquerque, New Mexico. The afternoon sunshine was a blazing contrast to the wintry Toronto weather I had left behind earlier in the day, but the dusty old building looked tired and rundown. At the stage door, two massive security men let me in, and I met tour manager Howard Ungerleider — Herms, to his friends — who was expecting me.

Together we figured out how this would work: I would be a silent observer, watching what went down from a privileged backstage position. I would travel one night with the band, and then overnight runs with the sound and lighting crews.

At that time, Rush was travelling with tour and stage managers, an accountant, some 35 roadies, three tour buses, and three tractor-trailers carrying 60 tons of equipment. The payload included 200 high-intensity lamps (24 of them identical to the landing lights on a jet), a $50,000 sound-mixing console, 64 speaker units and a rear screen-projection system to flash images of spaceships and floating figures. Not to mention dozens of guitars, miles of cables, and Neil Peart’s massive drum kit.

A separate crew had arrived late the previous evening, working overnight to install a huge stage tailored to the band’s requirements. The first members of the road team had arrived at 8 a.m. to hang the lights and the massive sound speakers. The crew that had built the stage was already on its way to install a similar stage for the following night’s show in Tucson, Arizona.

As an outsider, I was welcomed warily by the roadies; it was suggested I climb the scaffolding and cross the stage on the truss — 40 feet off the floor — that carried dozens of lights, and then climb down on the other side. Nearly 45 years later, I can’t remember that I did, but the crew eventually warmed to me anyway.

I watched the show slowly come together. Speakers were chain-hauled into the ceiling; the massive sound board was set up in the middle of the arena floor, two roadies set up the drum kit, others wound cables, shifted monitor speakers, and tested the sound system. (Road crews cannot count past two: “one, two; one TWO, ONE TWO” they say over and over into every microphone on stage. Apparently, no roadie has ever said “One two three…”)

In a barren space under the stage, a cafeteria space has been created, and Howard Ungerleider is not pleased. And an unhappy tour manager is not to be trifled with.

The local promoter has obviously not read the contract rider. This is a remarkable document — more than 200 pages in a loose-leaf binder — and it covers every single aspect of staging a Rush concert.

Much of it is technical information about electrical requirements, fire safety, regulations regarding special effects, explosive flash bombs and smoke machines. Other sections define dressing room dimensions, parking needs for the buses and the tractor-trailers, and the number of towels and bars of soap (Dial and Irish Spring, please) to be provided for the crew.

And, of course, catering. And this is why Ungerleider was unhappy.

Nearly a dozen pages of the rider relate specifically to the food and drink requirements for the band and the crew; full menus are set out, including three different meals for each day of the week. If it’s a Monday, the meal options are different from those on Tuesday. One crew member told me: “Heck, on this tour, the food we get is the only way we know what day it is.”

But on the day of my arrival, the care and feeding of band and crew was not what it should have been. The Sunday dinner was not the fresh roast turkey with stuffing, cranberry sauce and buttered green beans that the contract specified. Furthermore, the meals were not served on china by uniformed wait staff, but with plastic cutlery on paper plates by a local catering company apparently manned by hippies. Several members of the road crew were quite unhappy about it.

The band — which had arrived at four in the afternoon, with the stage set up finished and ready for sound check — ate the barely cooked beef without complaint.

However, Ungerleider had words with the head of the company that was promoting the entire tour. Apologies were offered and grudgingly accepted, and meals down the road in Tucson and Phoenix were almost up to the standards of a good French restaurant.

A quiet dressing room — calm before the storm

In the band’s dressing room, however, all is quiet — apart from a distant echo of an expectant crowd. The opening band has been delayed — bus problems, the bane of all tours — and they will miss the show; Rush will play an extra long set.

These three men don’t look like rock stars. Apart from a case of beer, some half-eaten sandwiches and a warm bottle of Dom Perignon, there are no signs of a bacchanalian feast. There are no drugs, apart from the Anacins that Neil Peart, the drummer, has just handed to one of the road crew. And there are no groupies.

Alex Lifeson, the guitarist, has his feet up on a chair and is smiling like a cherubic choirboy at nothing in particular. Geddy Lee, the bass player, horn-rims perched on his prominent nose, is reading Playboy, noting without much enthusiasm that Peart has shown up on the lower reaches of the new issue’s jazz and pop poll. “Behind Karen Carpenter, and you know what a good drummer she is,” he mutters.

Peart himself, wearing the bicycle clips that prevent his baggy pants from tangling with the bass pedals of his $15,000 drum kit, is totally immersed in yet another science fiction novel.

In the arena, the now full house is roaring: “Rush, Rush, RUSH!” Michael Hirsh, the stage manager, puts his head around the door, quietly says, “Ready in five,” and vanishes. Another roadie pops in and grabs a beer.

The three musicians, without a word, get to their feet. Only Peart, putting down his book and massaging his knuckles so hard that they crack, shows any sign of tension. As the three move into the arena, the lights go down and the roar of the audience turns into cheers. An eerie sound of howling space wind screams from the bank of synthesizers on stage, and a voice yells into the darkness, “Ladies and gentlemen. From Canada —welcome RUSH!”

With a stunning crash of noise, the band hits the first note as the lights, perfectly synchronized, flood the stage with bright, white daylight. The volume, bone-crushingly loud, builds as the band pounds into the first number of a show that will last, without pause, for exactly two hours and eight minutes. Geddy Lee, dancing now, hurtles toward a microphone and shrieks, “Hiya, Albuquerque! How're ya doin’?”

A magnesium flare cracks off with the sound of a thunderclap and a flash that singes the eyeballs. The backstage visitor, not understanding the roadies waving their arms at him in warning, stares directly into the flash, while the band and the crew, knowing exactly when it’s going to explode, turn their backs.

The fans, all 8,000 of them, are on their chairs now, punching their arms into the air with every beat. Security guards pull a young girl from the crush in front of the stage; she shakes her head, gathers her strength, and runs out from under the stage and into the audience again.

Lee, with a voice that sounds as if it had been scraped with used razor blades, is howling:

We are the priests of the Temples of Syrinx

Our great computers fill the hallowed halls...

Look around this world we’ve made...

“You know what this is?” one of the stagehands yells to the visiting writer. “It's a giant, mobile, crazy fucking circus. It's Barnum and Bailey, except it’s more work — and a hell of a sight more fun.”

±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±±

A postscript to the Rush story

The death of Neil Peart in 2020 signalled the final coda of the band’s long career, although the drummer’s retirement five years earlier had effectively taken the band off the road.

Geddy Lee, however, has written a cheerfully informal autobiography (My Effin’ Life, Harper Collins $50) that’s loaded with anecdotes and photographs and a touching story of his family’s survival of the Holocaust. Strongly recommended to all music fans.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

21 MORE THINGS A PUBLICIST CAN DO FOR NEW ARTISTS

In the last issue of Stories from the Edge of Music I included a list of 10 things a full-service publicist can undertake to help get a new artist to build a career. Here are 21 more — in no particular order of importance. And if you can think of more, please feel free to comment.

• Organize high quality photography of the artist.

• Hire video makers and other support people.

• Write grant applications (or find grant writers).

• More hand-holding (a.k.a., media coaching).

• Encourage a constant and consistent presence on social media — Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and, now, TikTok.

• Create an EPK (electronic press kit) including performance footage, interviews, etc. to send to fans, industry contacts, YouTube and people who could hire the artist to play clubs, concerts, festivals.

• Organize events to showcase the artist’s performance skills, songwriting, special qualities.

• Search media, online sites and reach out to contacts for opportunities for the artist.

• Arrange media interviews.

• Place the artist on the right TV and radio shows.

• Help launch new websites, streaming events, CD releases and video/film projects.

• Enable artists to connect with influential people, tastemakers, and other artists further up the food chain.

• Link the artist with record producers who might share your enthusiasm/support for the artist.

• Promote tours from here to there and back again.

• Helping the artist get opening gigs and headline appearances.

• Arrange media coverage in communities where the artist is performing, and set up key interviews in each market.

• Help find an agent.

• Help find a manager.

• Help find a music publisher.

• Oh, and hold the artist’s hand as they transition into more successful times.

• Finally, insist that the artist pay $750 - $1,500 a month for at least four months.

…And what should the artist ask the publicist?

Of course, it’s not a one-way street. The artist should ask questions. These are a few of them:

• Can the publicist write?

• Who are the publicist’s current clients?

• Who has the publicist worked with in the past?

• Does the publicist have strong personal contacts with media people?

• How well does the publicist relate to digital media, as well as with print, television and radio?

• What’s the publicist’s reputation with the media?

• Is the publicist well-known and respected in the various parts of the music industry?

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

A FINAL WORD

Well, not quite. Every now and then, I add “content” (God, how I hate that word!) for the paid subscribers to Stories from the Edge of Music. This time, another postscript to the story on Rush — some thoughts on groupies, the women I call the mythic figures of rock and roll.

(For paid subscribers only)

GROUPIES: THE MYTHIC WOMEN OF ROCK ND ROLL

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Stories from the Edge of Music to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.