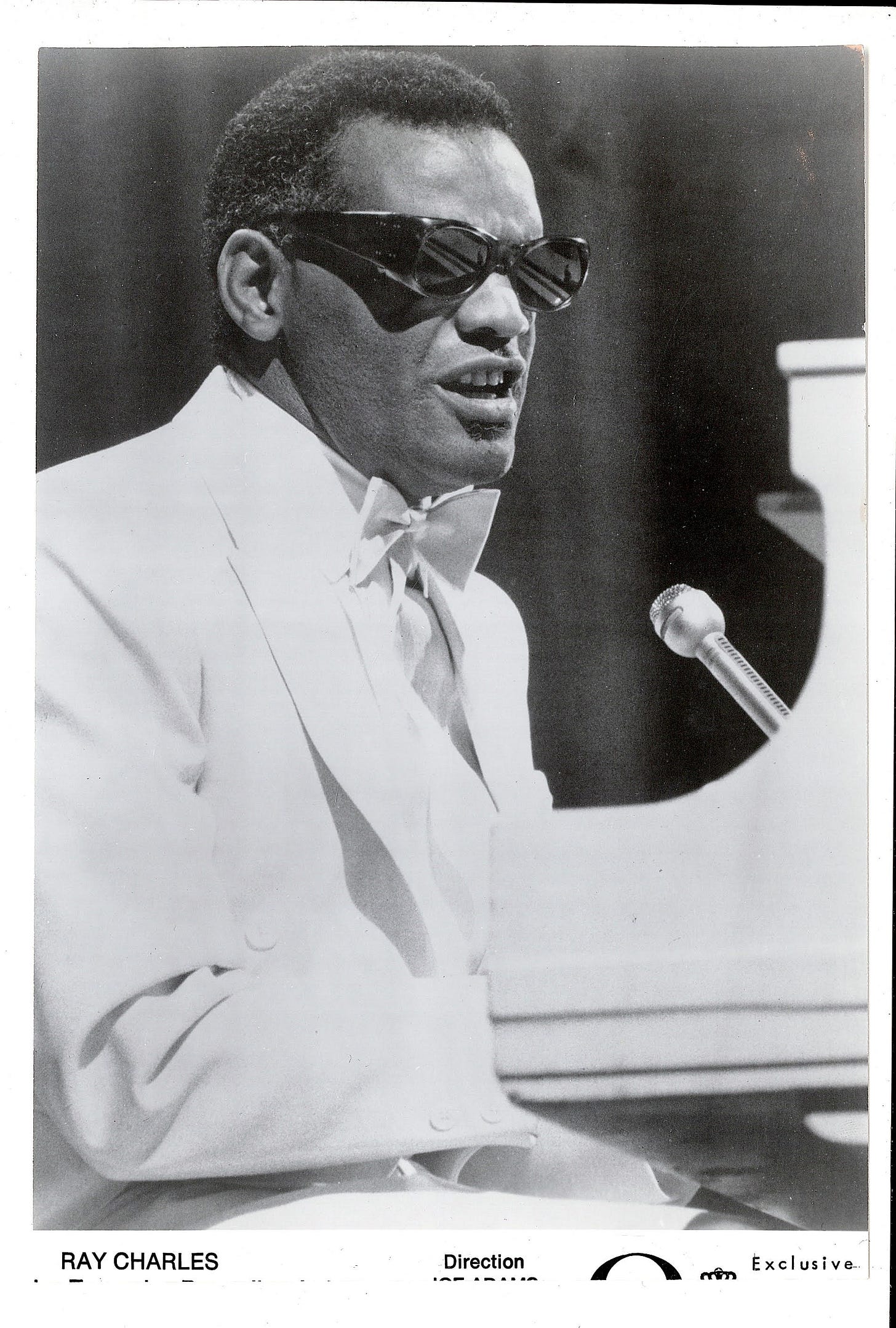

#12 Stories from the Edge of Music: Ray Charles

Hard sell, a soap opera as a hotel room guide, and a moment of desperate vulnerability

Back in the day, this music business veteran promoted some pretty amazing concerts at Toronto’s Massey Hall: B.B. King, The Chieftains, Bobby Blue Bland, Buddy Guy, Miles Davis, Tommy Makem & Liam Clancy and Maynard Ferguson among them. Flohil’s Massey Hall concert with Ray Charles was typical of the shows the r&b/jazz crossover artist presented in the ’70s… nothing spectacular, but really good. But the stories are still worth telling.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

HOW A SALES PITCH GOT RAY CHARLES TO TOWN

“Good morning to you! And how are you today?” When a voice you don’t know starts a telephone call like this, you know you’re about to be sold something…

The pitch continued: “This is Jay Adams, and I represent the fabulous Ray Charles, his world famous orchestra, and the wonderful Raelettes. We are anxious to perform in your beautiful community, and I am calling to suggest you consider bringing this superb attraction to your city…”

This is not the regular way of soliciting business from concert promoters. Agents never speak from a prepared spiel; they build workable relationships with presenters and they talk informally, learning to bury the pitch in between small talk and gossip.

Nonetheless, I was more than interested. Ray Charles had always been a hero, he had not appeared in Toronto for several years, and the date the irrepressible Jay Adams wanted was, in fact, available at Massey Hall. We made an agreement; my then-partner Ellen Davidson and I would promote two concerts with Mr. Adams’s client, one in Toronto and one in Hamilton, a nearby but separate market.

Charles’s checkered history of poverty, early blindness, mediocre Nat King Cole-styled records on a small label and crippling heroin addiction were all a long way behind him. His powerful records on the Atlantic label had made him a star, and the combination of blues, jazz and gospel music had made him an international attraction. The hits kept coming — “Hit the Road Jack,” “What’d I Say,” “One Mint Julep,” “Crying Time,” “Busted,” “Georgia on My Mind” — but by the time he played the two shows in Canada, his career had slowed down.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

A star arrives, and so does the RCMP

Two months after the initial sales pitch, Ray Charles’s private jet taxies to an outlying hangar at the Toronto airport.

The nervous promoter is waiting in the immigration department at the main terminal. Back in those days you could do that — years later, security concerns made going “backstage” at an airport as difficult as trying to enter Fort Knox with a machine gun.

As two mini-buses arrive with Charles, Adams, the band members and the three red-fingernailed Raelettes, the customs and immigration staff let them through with hardly a question, although two or three of them do ask for the bandleader’s autograph, which he signed with a flourish.

The promoter, the star and his ebullient manager settle into the waiting limousine at the airport, but as we are about to drive off, the car door is jerked open. “Sergeant Jenkins, Royal Canadian Mounted Police,” a uniformed officer announces. Charles stiffens, turning his head suddenly; Jay Adams looks shocked, and the promoter looks confused. Oh, God, not a drug bust, all three of us think, simultaneously.

“Just wanted to welcome you to Canada, Mr. Charles. I hope you have a successful show,” says the police officer, gently closing the limousine door. There is an audible sigh of relief as the limo pulled away.

As the limousine pulled up to the Sutton Place hotel — now turned into yet another Toronto condo development — I was able to watch the “star treatment” that celebrities encounter every day of their lives. The registration formalities had been done before the star’s arrival; the uniformed doorman took the luggage from the trunk of the car, the hotel manager appeared to greet us and walk us through the lobby to the elevators. There were fresh flowers and chocolates and a chilled bottle of champagne waiting in the Prime Minister’s Suite.

I’d already booked the suite through Ann McRoberts, the hotel’s publicist. When she told me the suite cost $500 a night — quite a sum in the mid-’70s — I pointed out that the person who would be staying there was blind and wouldn’t be able to see the luxurious accommodation. She laughed and let me have the suite for a third of the price.

As we entered the suite, Charles asked if we could turn the television on. “If the TV’s on, I can figure out where everything is,” he said.

As we slowly walked him through the suite’s three rooms, an afternoon soap opera was his guidepost.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

A 10-second moment of confusion and terror

The show itself offered few surprises to the sold-out crowd at Massey Hall. With a dazzling smile, Charles ran through an hour and a half of his hits, interspersed with extended jazz-based pieces. The Raelettes, elegantly gowned, were the visual centerpiece; the band itself — a dozen players — was precise, disciplined and suitably funky.

However, the “world famous orchestra” lacked distinguished soloists. David “Fathead” Newman, who was the tenor sax player on many of Charles’s memorable records, wasn’t present and the players seemed to go through the motions.

Even Charles himself, even with his thousand-watt smile, seemed distracted and strangely disconnected from the songs — maybe, I thought as I stood in the wings, he’s just played them too many times, in far too many places around the world.

In the intermission, one of the horn players asked if I had any weed. “Man, Ray’d fire my ass in a heartbeat if he knew I’d even asked. He’s pretty uptight about that, which is cool enough, and I understand. But, man, a toke would be really nice…”

On stage, Charles sat at the piano at stage left, close to the wings, playing chords and occasional punchy solos, directing the band and the backup singers with nods, encouraging smiles and occasional hand gestures. As he sang, he moved strangely out of sync with the music, as if he were hearing rhythms that his audience could not; other blind artists, including Stevie Wonder and the late Jeff Healey, moved in the same apparently uncoordinated way.

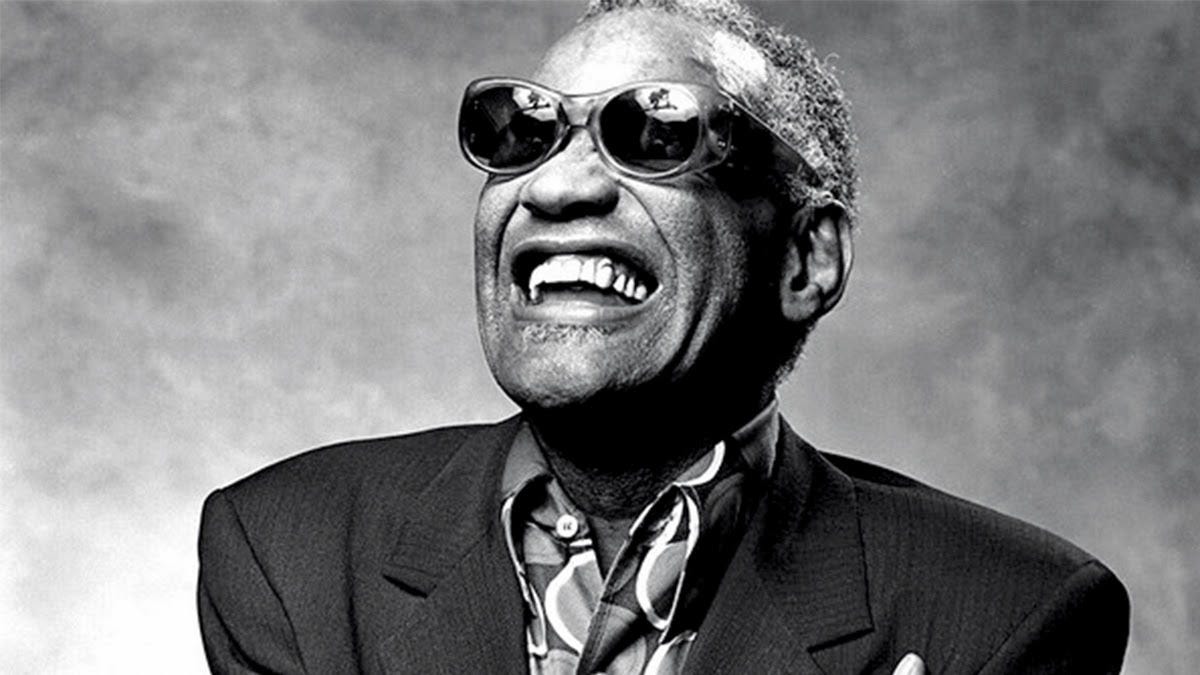

Nobody ever saw a photograph of Ray Charles without his dark glasses, just as we’ve never seen a photograph of Dolly Parton without yet another spectacular blonde wig. As he came to the end of his show the following night at Hamilton Place, he stood up from the piano, faced the audience, and raised his clasped hands above his head in the way that boxers do when they win a fight.

As he did so, he accidentally knocked his dark glasses off.

For a brief moment, those nearby — and I was standing in the wings 15 feet away —saw the terrified expression on his face as he turned, apparently helpless, away from the audience. Within seconds, his guitarist picked the glasses up, pressed them into Charles’s hands, and they were back on his face.

The smile returned, the confidence was back and a standing ovation rewarded the performance. But, for perhaps ten seconds, we had seen a frightened, vulnerable person, briefly deprived of his defence against the world.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

A quick postscript

Two days after Charles had moved on to yet another show in yet another city, I noticed a report in the newspaper that the New Zealand government had denied him entry for an upcoming tour, citing his drug addiction.

Furious, I wrote a stern note to the New Zealand embassy in Ottawa, pointing out that the artist had just completed two sold-out concerts in Canada, and that he was totally drug free (and a stern disciplinarian as far as his band members were concerned). The decision was discriminatory and robbed people of the rare opportunity to experience the music of a major star, I added; I sent a copy of the letter to his manager.

Three months later, I received a phone call. “Good morning to you! And how are you today?” said a familiar voice. “This is Jay Adams, and I represent the fabulous Ray Charles, his world famous orchestra, and the wonderful Raelettes. We are anxious to perform in your beautiful community, and I am calling to suggest you consider bringing this superb attraction to your city…”

I interrupted, reminding him that only three months ago, my partner and I had just presented Ray Charles at Massey Hall, as well as at Hamilton Place. I declined; it was much too soon to return. “Well, thank you very much,” Adams said, hanging up.

Within weeks, Ray Charles — this time presented by a different promoter — played Massey Hall again. There were fewer than 700 people in the audience; a significant amount of money would have been lost.

Nonetheless, I was sure that Jay Adams would still be working the phones, making sure that Ray Charles was playing, somewhere in the world, almost every night.

Which he did, until he died in June 2004.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

A MUSIC FESTIVAL STORY: NEVER ON SUNDAY

Rosalie Goldstein was a powerhouse. The artistic director of the Winnipeg Folk Festival, she was maybe five feet four inches tall, wide, and crowned with bright red hair and spectacular purple glasses. She had succeeded Mitch Podolak, the festival’s founder, and she was not a woman to be trifled with.

So, let’s time-machine back to the opening Friday afternoon of the 1987 festival.

Suddenly, Goldstein is approached by a small feisty woman, who does not look happy; she’s the manager of the Scottish roots rock band Runrig, due to headline the Saturday night main stage show.

“What’s this?” the woman demands, jabbing at the festival’s printed program. “Workshops? What’s that about? And on a Sunday, too…” Well,” Rosalie explains, “workshops are collaborative on-stage meetings of different musicians, who might talk about the songs they’ve written, demonstrate instrumental techniques…”

The unhappy manager breaks in. “I know what workshops are,” she says. “The people play and sing on these Sunday workshops, right? You’ve got my lads down here for Sunday shows, right? Well, they won’t do them.

“They’re all members of the Wee Free Kirk o’ Scotland, and they cannae do their job on Sunday. It’s a religious commitment. They can play football, they can chase lassies, or whatever, but they cannae do their job, and their job is playing music. That’s final — my band’ll play no shows on Sunday!”

Furious, Goldstein now has to rewrite the entire Sunday afternoon workshop schedule, arrange other artists to fill the spots that Runrig would have played, and — it’s too late to change the printed program — have the changes announced at all the festival’s five stages.

On Saturday night, Runrig hits the stage at 11 o’clock and plays a storming set — this band is not known as Scotland’s Bruce Springsteen for nothing. The audience is on its feet, cheering, applauding, demanding more. The band’s manager runs up to Goldstein, standing at the side of the stage.

“You’ve gotta get them back up for an encore,” she shouts over the screaming crowd. “You gotta send ‘em out again!” Rosalie Goldstein looks at her watch, and leans close to the manager’s ear.

“Two minutes past midnight,” she says.

“It’s SUNDAY.

“So FUCK OFF!”

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

SOME VIDEO LINKS TO CHEER UP YOUR WEEKEND

Ray Charles does the “Mess Around”

Ray Charles sings the Beatles

Runrig sings a Canadian song

(This song was a major hit for Rod Stewart, and was written by two Canadian songwriters, John Capek and Marc Jordan.)

Runrig’s last concert

(Runrig disbanded in 2018. For the last 20 years of the band’s existence, the singer was Nova Scotia’s Bruce Guthro, who died of cancer a couple of months ago, in September 2023.)

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

WHAT YOU’LL GET NEXT WEEK

The first of two instalments full of stories about the early days of a pioneering independent artist, Ani DiFranco. A self-styled “baby dyke,” she really began her career in Toronto. There’ll also be a story about the leading music publicist in Canada back in the day — and, no, it wasn’t me! Tune in, tell your friends and share it if you’d like to.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

A SHORT NOTE ABOUT STORIES FROM THE EDGE OF MUSIC

To my amazement, these Stories from the Edge of Music seem to have found an audience — 56 new people have signed up since November 1. Most of almost 400 subscribers (in less than three months!) read this stuff free of charge, and I’m delighted to share this with them. A little more than 50 folk are paid subscribers, however, and the modest income helps top up my old age pension, which is both good news and something of a relief!

Next week, I’ll be adding additional “content” exclusively for the paid subscribers. It’ll probably turn out to be more personal stuff — about friends, life, death, sex, drugs and some rock and roll. If you think this might be interesting (and I hope it will be!), consider becoming a PAID subscriber. At $6.00 a month — the price of a couple of coffees at Starbucks — it helps keep the stories coming and is greatly appreciated.

Very interesting Ray Charles story, Richard! Looking forward to reading about Ani Difranco...