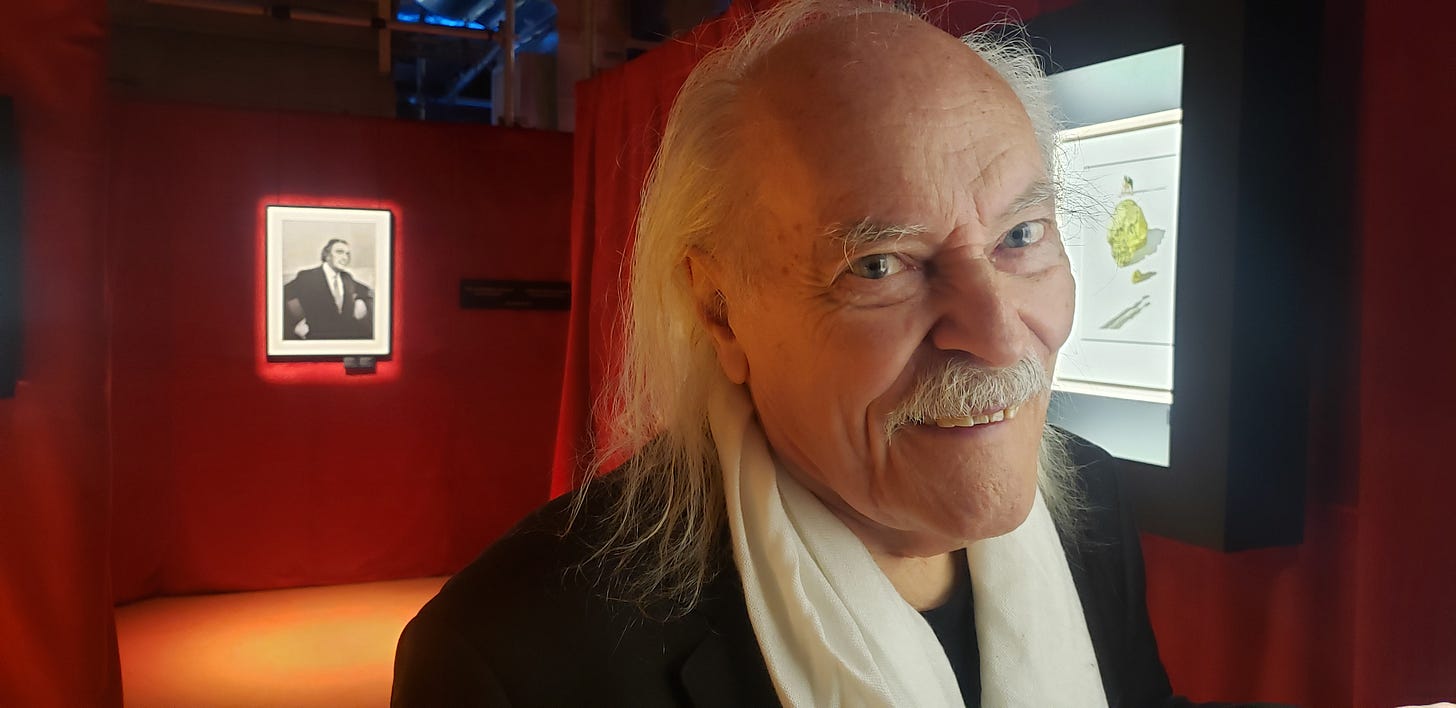

HERE’S AN INTRODUCTION

Stories at The Edge of Music is a regular collection of pieces about artists I’ve met and often worked with. I can’t sing, can’t play an instrument and dance like a pregnant bison — but I’ve always been fascinated by music and the men and women who make it.

Many of them are no longer walking this earth, but the music they made can be heard on whichever medium you use to listen to music — vinyl EPs and LPs, CDs, YouTube, Spotify, Apple Music etc. And their stories still resonate.

Some personal background stuff: I started to work as junior newspaper reporter in the north of England when I was 16, and moved to Canada in my early twenties for two reasons. First, Great Britain in 1957 was grey and boring and wet and class-ridden and certainly no longer great. Second, I wanted to meet those iconic blues artists with strange names who I had heard on records as a teenager — Muddy Waters, Sleepy John Estes, Robert Nighthawk and Howlin’ Wolf among many, many others.

I couldn’t get newspaper work in Toronto but I edited trade magazines, travelled from coast to coast, and began to bring my musical heroes to Canada, slowly starting a career promoting and managing local artists, presenting concerts and writing entertainment articles for anyone who’d buy them (especially for the Toronto Star). In 1970, more than half a century ago, I was made editor of a music magazine (The Canadian Composer/Le compositeur canadien), which thrust me into the middle of a rapidly developing Canadian music industry. I held that half-time job for 22 years.

Enough about me. Hang in; there’ll be word portraits of musicians as diverse as Miles Davis and Stompin’ Tom Connors, Louis Armstrong and Loreena McKennitt, the Downchild Blues Band and Charlie Watts, Alice Cooper and Ray Charles, comedian Billy Connolly and Nana Mouskouri. And more — much, much more.

I’m old now, and at 89 I’d better set these pieces down while the memory still works. So why don’t you dive into story #1, about the greatest soul singer of them all…

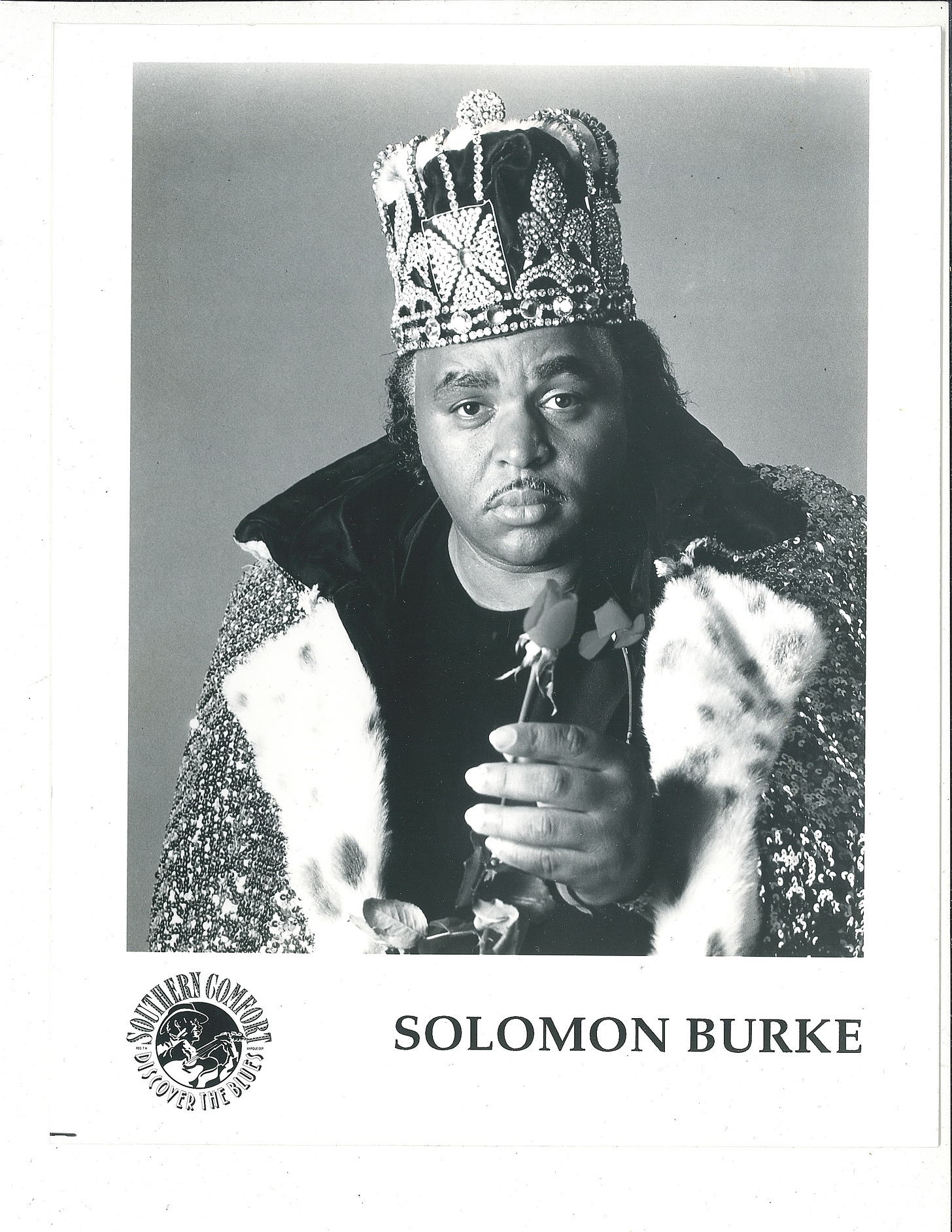

SOLOMON BURKE: THE KING OF ROCK AND SOUL NEEDS TWO DOZEN RED ROSES, A RED CARPET AND A THRONE

It’s 10 in the morning, in the dusty lobby of the Airport Ramada Inn in Edmonton, and a beautiful black girl/woman is in conversation with a volunteer from the Edmonton Folk Music Festival.

“Have you got the roses?” she asked.

“Roses?” he responded, with a surprised expression.

“Yes, the red roses.” She paused. “The carpet? You have the red carpet?”

A blank look crossed the face of the volunteer, a young man in his mid-20s. His consternation increased when she spoke again: “What about the throne?” she asked.

“Look,” she said, losing patience, “have you read Bishop Burke’s contract?” The hapless volunteer admitted he had never seen it.

“Never mind,” she responded. “My father requires two dozen red roses, two silver vases for the roses, a red carpet — and a throne.

“Otherwise, there will be no performance.”

She turned and walked away. Then she looked back: “Please make sure that you cut off all the thorns on the roses.”

Miraculously, when Bishop Burke — much better known as Solomon Burke, the self-styled King of Rock and Soul — headlined the show that night, the throne, the roses (thorns removed), the silver vases and the red carpet were all in place.

I had first heard Solomon Burke in the early ‘80s in a club called the Blue Note, hidden in a pillar-ridden room under an apartment building in Toronto. Burke’s performing life had begun as a seven-year-old boy preacher in Philadelphia, but had taken off spectacularly in the early ‘60s.

As the pride of Atlantic Records, he had hit after hit after hit, but at this point, in a dingy basement, his career was at rock bottom. The venue was almost full, but that meant there were, perhaps, 80 people in the place.

Two years later, he played for a week in a now-vanished night club in midtown Toronto, accompanied by a local band with a horn section. Linda, my girlfriend at the time, refused to go — she hated trumpets, she explained. She missed a staggering night of music.

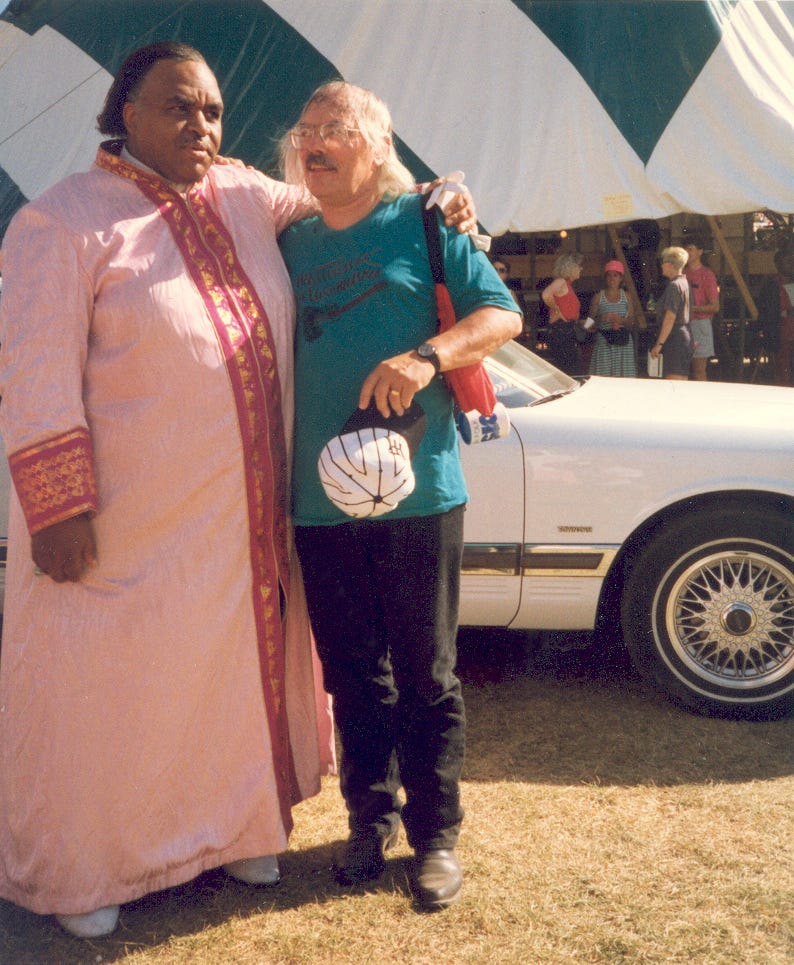

I booked Solomon for the second Southern Comfort Blues Festival in Toronto in April 1991, and he showed up with his musical director for the rehearsal with 10 local players. The run-through was astonishingly brief — he handed out charts, rehearsed his opening song, instructing the horns to quiet down at one point. As the bass player adjusted notes on his chart, Solomon said, amiably, “Hey, man, don’t lead — just follow!” After 20 minutes, he called a halt. “Look, you fellas know the tunes. Just follow me. And everything’s in G… See y’all tonight.”

He and his colleague climbed into their limo and left. As I sat backstage prior to his show, carefully slicing the thorns off the two dozen red roses, which he would throw to the prettiest women in the audience, I realized that I still hadn’t got the measure of the man. I also thought that it was just possible that he would make some last-minute demands — for more money, or a well-cooked steak — but I need not have worried; Solomon Burke was the consummate professional. And the makeshift pick-up band performed perfectly, losing its way only once, for just a few seconds, when the singer, without warning, suddenly launched into a Little Richard medley.

The first time Burke played the Edmonton Folk Music Festival, in 1990, he came with four of his 21 children — three daughters and a son, Haile Selassie Solomon Burke III. He rehearsed in the afternoon with the Festival House Band led by Amos Garrett, and I recall the drummer coming out of the makeshift rehearsal room and telling me: “You’re not going to believe the show tonight!”

The audience for the Friday night show, who had never heard of him, was nonplussed. At 400 pounds, Burke cut an imposing figure as he slowly made his way to the throne at centre stage, wearing a floor-length purple velvet cape, trimmed with white fur (and, incidentally, lined with silver dollars in transparent plastic sachets).

As the performance got underway, he would keep singing as his son stepped forward to wipe his father’s forehead with an immaculate white handkerchief. Halfway through the 45-minute set, the audience was rocking, and he imperiously summoned the closing artist, blues singer Koko Taylor, to the stage. She acknowledged the audience and was promptly shooed away as Burke cheerfully upstaged the headliner.

The following afternoon on a small stage in the pouring rain, Solomon once again stole the show. At the session, hosted by Barrence Whitfield — a wonderfully off-kilter singer from Boston — Burke appeared without warning, wearing a huge Stetson hat and with his floor-length gabardine raincoat draped around his shoulders. Whitfield bowed to him, and left Solomon to it.

With the house band faithfully backing him, Burke launched into a 15-minute song (with a few bars from each of his major hits) about Edmonton, about the musicians, about the pouring rain, about his 21 children, about God and lust and love and peace — half sermon, half gut-bucket blues. When he ended the song, he strode off and parked himself, under cover, on a canvas chair next to the stage.

It fell to Rita Chiarelli — substituting for singer Ruth Brown, who had refused to leave her hotel room because of the weather — to follow a jaw-dropping performance and appease a rain-soaked audience demanding more.

Rita is blessed with a four-octave voice with the strength, power and volume to stop an elephant at 60 paces, and she walked out, hit a high, wailing note, and held it for what seemed like minutes. The audience cheered, and one masterful song was followed by another.

In his chair, Burke tugged my sleeve.” Who IS that?” he asked. “Where’s she from?” Toronto, I responded. “Well,” he summed up, “if I ever work for you again in Toronto and that young lady don’t open my show, your ass is in a sling.”

On the Sunday morning gospel show, he shared the stage with the aptly-named blues shouter Big Miller, an old friend from Daddy Grace’s church in Philadelphia and who now made his home in Edmonton. Before Miller advised him not to, Burke wanted to take up a collection. Instead he sent three of his daughters, young teens at the time, into the audience giving out bright red Bible bookmarks. The girls looked as if they would much rather be shopping at the West Edmonton Mall but their father had given instructions and they obeyed.

After his final set with the house band, Burke called each member, one by one, into his trailer. Thanking them, he shook them warmly by the hand, palming each of them an American $100 bill.

When Solomon Burke returned to the Edmonton Folk Music Festival four years later, the buzz was all about Joni Mitchell, due to make a rare live appearance. But it was Solomon who once again stole the show, closing the Saturday night concert (and going well over the festival’s closing time curfew). With a huge band, with four horn players, three of his children as backup singers (grownup, and now looking like they were enjoying themselves), a blind keyboard player (the double of a teenaged Stevie Wonder), a powerhouse rhythm section and a tall blonde woman who played concert harp, Bishop Burke was in his roaring element.

As he slowly walked on stage, one of the horn players stepped forward, took the massive velvet cloak from Burke’s shoulders, and spun it offstage like a cartwheel — a move that took mere seconds, and one which many in the audience may well have missed given how quickly it happened.

And he closed the show with 50 audience members onstage, dancing to soul music that had had its heyday three decades before.

In his trailer after the show, I told him how much I had enjoyed the move with the cape. “Ah,” he responded, “back in the day, back in the day when I was playing big stages, we had a dwarf in the band called Little Sammy.

“Sammy would walk behind me, under the cape, when I came on. Then I’d wait a few moments, drop the cloak, step toward the throne, and the cape would move offstage, just all by itself as far as the crowd knew. Nobody ever figured there was a midget under the cape…”

The last time I saw Solomon, now weighing 450 pounds and largely immobile, was at a blues festival in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. My friend Dick Waterman had persuaded the organizers to have me host a workshop on the future of the blues, but when I discovered that Burke was headlining the event, I suggested I do an interview with him on one of the daytime stages. They agreed, and I phoned his office in Hollywood.

“Bishop Burke is in Europe,” said an assistant. “He will call you when he returns.” He did, but I was on holiday and missed his call; we never did connect. Until, backstage at Fort Lauderdale, be beckoned from the front seat of his limousine. I walked over, he shook my hand warmly, and asked, “So, why were you calling me?” I explained, he shrugged, and we went on to talk of other things — our children, his overseas tour schedule, and his church, Solomon’s Temple: The House of God for All People. He pointed out that he had churches in most major American cities and missions in many smaller communities.

“Sometimes,” he said, in the rising cadence of so many black preachers, “sometimes, sometimes, I will be playing a secular gig, and someone will come to me and introduce himself as the pastor of my church in the community. Often they will say ‘I have my tithe with me’ — it may be only $100, but I always accept it.”

Suddenly, everyone backstage was asked to leave. Light rain was falling. A select few crew members lifted Solomon out of the limousine, placed him in a wheelchair, and carefully positioned it on the tailgate lift of a truck and raised the singer onto the stage. Behind a hastily-erected black screen, he was transferred to the throne at centre stage. Seconds later, the curtain dropped — and with a slight hand motion Burke signalled the band to power into action.

Solomon Burke’s “Soul Survivor Orchestra” was as tough and tight a band as ever played the rhythm and blues circuit. The opening song — Everybody Needs Somebody to Love, later made famous by the Blues Bothers — galvanized both the band and the audience that afternoon in Florida. Despite the rain, most people were up and dancing, as the tune segued into a medley of his hits.

Then, with a single command — “Eee-sy” — the band powered down to a whisper. Burke cupped his hand to his ear, leaned forward on his throne, and began to sing an old country hit: “Put your sweet lips to the phone… Mr. Flohil.”

Name checked by the greatest soul singer of them all! I was surprised, elated, impressed and complimented, all at once. And my pal Dick Waterman, taking shelter from the rain, missed it…

Starting yet another European tour, Solomon Burke died at Schiphol Airport in Amsterdam as his plane landed. Sitting in front of my computer in my office, I saw the first notice of his passing as it spread across the Internet. It was Sunday, October 20, 2010.

And, presumptuous as it may sound, I felt I had lost a friend.

THIS WEEK’S REMARKABLE VIDEO

This video is a reminder of the remarkable talents of Slim Gaillard, a now forgotten pianist, guitarist and songwriter. He was also a man who invented his own language, Vout-o-Reenee, some of which you can hear on this video, which I guess was made in the late ’40s. (He also spoke no less than eight foreign languages.)

Best of all, he had a sly sense of humour — and the longest fingers of any pianist I’ve ever seen:

Oh, and there’s an excellent bio of Gaillard here.

UNTIL NEXT TIME

So, there you have it — the first Stories at the Edge of Music.

Next time (give me a week to 10 days), you can read tales about Alice Cooper and Nana Mouskouri, and soon paid subscribers can read a surprising story about Miles Davis. Your comments are welcome; my e-mail is rflohil@sympatico.ca

Yay!! So happy for you and proud of you for doing this. The world needs to hear these stories! Soul filling. XO

Love it Flo! Keep ‘em coming!